2022 UPDATE: After this story was originally posted in 2016, Lt. Rita M. Knecht, LAPD, Ret., used her outstanding research skills to locate a wealth of information on the lives of Robert William Stewart, Joseph Henry Green and their families, as well as LAPD Chief John Malcolm Glass. I have added the results of Lt. Knecht’s research in this blue font. Thank you, Lt. Knecht, for contacting me and for your interest in L.A.’s first two black police officers. Thanks also to genealogist Lyndsey Stewart for sharing Ellen Doty’s death certificate. I am also grateful to a trio of Indiana librarians – Andrea Glenn at the Indiana State Library, Diane Stepro at the Jeffersonville Library, and Meghan Vaughn at the Floyd County Library – who were extremely helpful with researching Robert Stewart’s years in Jeffersonville, Indiana.

Most importantly, at the urging of Los Angeles Police Chief Michel Moore, on February 23, 2021, the Los Angeles Police Commission voted 5-0 to ceremonially reinstate Stewart as an officer and retire him with honor. In addition, on February 2, 2022, the roll call room at LAPD’s Central Station was named for Stewart. As of March 2022, however, the LAPD website’s history section still wrongly asserted that Robert Stewart was hired in 1886 and that he was the first black police officer in the United States.

* * * * *

When this story was first posted in 2016, the Los Angeles Police Department

website said that Robert William Stewart and another man, Roy Green, were both

hired in 1886 as the LAPD’s first African-American officers. However, the exact evidence substantiating

the 1886 date has never been published or even described. In addition, Los Angeles city directories printed

in 1886 and 1887 list the members of the Los Angeles Police Department, but

neither Stewart nor Green is among them.

Recent research using publicly available resources shows

that Robert William Stewart and Joseph Henry Green – not Roy Green – were both

appointed LAPD officers on March 30, 1889. Stewart and Green definitely share the title of the first

African-Americans on the LAPD, although three years later than previously

believed. Available documentation suggests that Stewart and Green were probably also the first black police officers in California.

Joseph Henry Green was dismissed from the LAPD on February 18, 1890, as part of a reduction in the size of the force. Less has been discovered about his life than Stewart’s, but we know Green was born in North Carolina on October 30, 1850. He was likely born a slave, possibly in Wilmington, NC, where he was living in 1870. By 1876 Green was in San Francisco, working as a waiter at the new Palace Hotel. He stayed at the Palace until about 1882 – also probably the year he was married – then spent around a year atop Nob Hill as butler for Mary Hopkins, widow of railroad baron Mark Hopkins.

Green moved to Los Angeles by the end of 1883 and became head waiter at the Pico House. Green helped to organize L.A.’s “Colored Republican Club” in 1886; his political activities helped him obtain the patronage appointment of Los Angeles City Hall janitor in 1887 and be chosen for the LAPD in 1889. Following his short service as a police officer, Green went back to being a waiter, and by 1902 Green was head waiter at the Hotel Rosslyn on Main Street. On Friday morning, July 17, 1903, Joseph Henry Green died at his home after what the Los Angeles Herald described as a “prolonged illness.” His cause of death was given as kidney disease at age 52 years, 9 months, and 14 days, and he was buried at Evergreen Cemetery in East Los Angeles. He left a widow, Amanda, and daughters Lauretta and Cecil.

Green moved to Los Angeles by the end of 1883 and became head waiter at the Pico House. Green helped to organize L.A.’s “Colored Republican Club” in 1886; his political activities helped him obtain the patronage appointment of Los Angeles City Hall janitor in 1887 and be chosen for the LAPD in 1889. Following his short service as a police officer, Green went back to being a waiter, and by 1902 Green was head waiter at the Hotel Rosslyn on Main Street. On Friday morning, July 17, 1903, Joseph Henry Green died at his home after what the Los Angeles Herald described as a “prolonged illness.” His cause of death was given as kidney disease at age 52 years, 9 months, and 14 days, and he was buried at Evergreen Cemetery in East Los Angeles. He left a widow, Amanda, and daughters Lauretta and Cecil.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Robert William Stewart was born a slave on March 1, 1850, near Lancaster, Garrard County, Kentucky (about 75 miles southeast of Louisville). He was the eldest of his mother's 11 children, eight of whom lived to adulthood. His parents were Faulkner Stewart (born c. 1804-1817, died 1900) and Ellen Doty (1830-1914), illiterate slaves who began living as husband and wife in 1849. However, they could not marry until Kentucky legalized marriages for blacks in 1866. [1] In September 1867, after most of their children had been born, Faulkner and Ellen received a Commonwealth of Kentucky “Declaration of Marriage of Negroes and Mulattoes.” It cost 50 cents to have their union officially recorded, plus another 25 cents for the certificate, significant amounts for newly freed slaves. [2]

|

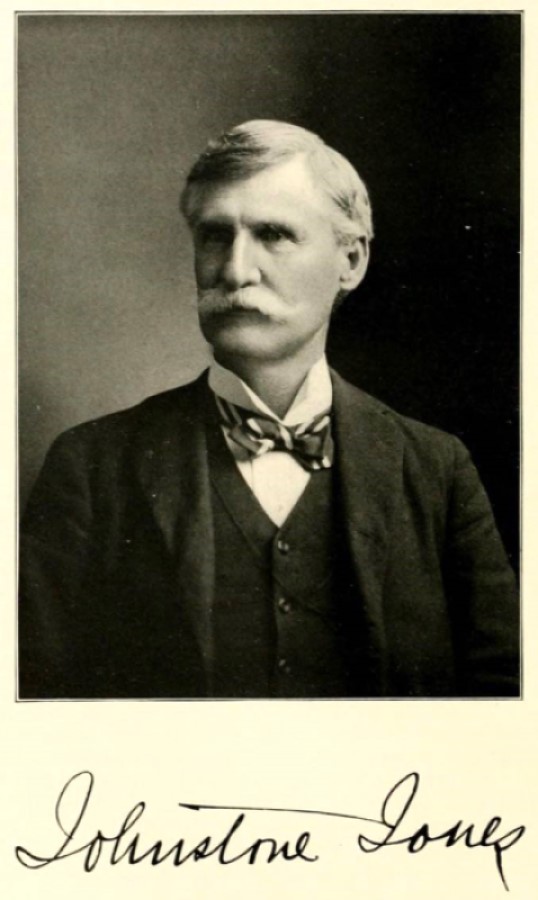

| This photo of Robert William Stewart was likely taken when he was in his twenties. |

It is unclear who owned Robert Stewart when he was born. However, it may have been Sabritt Doty (1806-1873), a white farmer and stock raiser who owned 10 slaves in 1850 and 18 in 1860. Soon after Ellen Doty’s son Faulkner Jr. was born on December 6, 1855, about five miles east of Lancaster near Back Creek, Sabritt Doty registered the birth to establish his ownership of the child [3]. Since Robert and Faulkner Jr. were brothers, it is quite possible Sabritt Doty owned them both, along with their mother Ellen (the surname of slaves was frequently that of their owner at the time they were freed). Their father, Faulkner Stewart Sr., likely worked at a nearby plantation or farm and had a different owner than his wife. His owner must have given him a pass that allowed him to travel.

Robert’s last sibling to be born in Garrard County was his brother Harve in July 1858. Robert’s sister Elsie was born c. August 1860 in Stanford, Lincoln County, the next county southwest of Garrard, as were the rest of his siblings (Stanford is about eight miles southwest of Lancaster). Because an 1851 Kentucky law required emancipated slaves to leave the state, [4] it can be assumed that c. 1858-1860 Ellen Doty and her children were sold, or possibly rented, to someone in Lincoln County; Sabritt Doty and his extended family appear to have lived only in Garrard County, not Lincoln County.

While little is known of Robert Stewart’s early life, information about where he grew up is available. When Stewart was born in Lancaster in 1850, its population was listed as 700, and Garrard County was home to 3,176 slaves, 25 free blacks, and 7,036 whites.[5] The county’s staple products that year were corn, rye, wheat and oats, and its main exports were horses, mules, cattle, hogs, and sheep.[6] When Stewart was a baby, Harriet Beecher Stowe visited Garrard County to do research on slavery before she wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Lancaster had no rail service when Stewart lived there.

By the time Stewart was living in neighboring Lincoln County in 1860, it had 3,430 slaves, 158 free blacks, and 7,059 whites. Stanford’s population in 1860 was 479, on its way to 752 in 1870, when Lincoln County’s population was 3,404 blacks and 7,871 whites. The county’s leading agricultural products in 1870 were cattle, hay, and mules.[7] Railroad service to Stanford began when the Louisville and Nashville Railroad reached town on May 17, 1866.

As far as is known, Robert Stewart spent the entire Civil War in Stanford, Lincoln County, Kentucky. He may have seen Federal troops march south through Stanford in mid-January 1862, on the way to their victory at the January 19th Battle of Mill Springs about 40 miles south of Stanford. The largest battle in Kentucky during the war, the Battle of Perryville, was fought about 20 miles northwest of Stanford on October 8, 1862. After this battle Union forces followed the retreating Confederates to the east and south, and U.S. Army records note that there was fighting at Stanford on October 14.[8]

Stewart may also have seen Confederate raiders stealing horses and cattle near Stanford in late March 1863 [9], prior to the Union victory 30 miles south at the Battle of Dutton’s Hill on March 30. Stanford was briefly taken by Southern raiders on July 31, 1863 [10], but they were soon driven out. Although other raids and skirmishes occurred in and around Stanford during the war, it appears no one in the Stewart family was a victim of the war’s violence. Robert and his father also should have been exempt from an August 1863 U.S. Military Order that authorized impressing Lincoln County slaves to work on extending the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. The order applied to slaves aged 16 to 45, so Robert would have been too young and his father, Faulkner, too old.[11]

President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to Kentucky, and we do not know exactly when Robert and his family were freed. Robert’s mother gave birth to his two youngest sisters in Stanford in July 1864 and August 1865, so his family did not flee north to escape slavery. Additionally, Robert’s father Faulkner did not serve in the Union Army, so a March 1865 federal law freeing the wives and children of black soldiers [12] would not have applied to Robert and his family, who may have remained slaves until the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, was ratified by Congress in December 1865 (The Kentucky legislature rejected the amendment in February 1865).

In post-Civil-War Kentucky, the Ku Klux Klan and other white “regulators” used violence to restore the commonwealth’s antebellum political and social order. Although blacks were the primary victims, white Republicans and Union veterans were also targeted. One such episode occurred in Stanford on July 18, 1867, when James Bridgewater, a major in the Union Army then working for the Freedmen’s Bureau, was shot and killed by regulators while he was playing checkers in a barroom. Kentucky Governor John Stevenson sent armed units to Lincoln County in 1869 to stop mob violence, but the Kentucky legislature took little interest in quelling the lawlessness. [13] In March 1871, a group of black citizens living in and near Frankfort, the state capital, petitioned Congress for protection from the Ku Klux Klan. The petition listed over 100 incidents in which blacks were murdered, attacked, or intimidated, nine of which occurred in Lincoln County between August 1868 and April 1870. [14]

There are different figures for the number of blacks lynched in Kentucky after the Civil War. One author calculated there were 117 documented lynchings in Kentucky between 1865 and 1874 (with many more undocumented and uncounted). Another historian has estimated there were 93 lynchings in the state from 1867 to 1871. Still other accounts noted that from 1867 to 1871, as many as 25 lynchings per year occurred in central Kentucky alone, mostly in rural areas near cities like Danville, which is just 10 miles northwest of Stanford.[15]

Robert Stewart is listed on the 1870 U.S. Census (enumerated on June 18) as working on a Stanford-area farm where he lived with his parents and siblings. Based on census records and an 1879 map of Garrard and Lincoln Counties at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, in 1870 the Stewart family appears to have lived about five miles northwest of Stanford between Hanging Fork Creek and the Lincoln/Boyle County Line, roughly halfway between Stanford and Danville. The land they farmed was probably owned by Dr. George Woolfolk Givens (1818-1881), a pre-war slave owner and Confederate Army surgeon. Dr. Givens does not appear to have owned Robert Stewart in 1860, and his family may not have moved onto Dr. Givens’ land until after the Civil War. The Stewart family’s association with Dr. Givens could have helped them escape being targeted for violence by the KKK.

On the 1870 U.S. Census both Robert Stewart and his eldest younger brother, Faulkner Jr., are shown as being able to read and write. However, subsequent censuses show Faulkner Jr. could not read or write, and it is almost certain that in 1870 Robert was not fully literate. Exactly when he received his education is unknown. Robert may have attended one or more of the Freedmen’s Bureau schools established in Kentucky by the Federal Government in 1866. A freedmen’s school in Danville in neighboring Boyle County may have been closer to his home than Lincoln County’s freedmen’s school, which was about 10 miles southeast of Stanford in the town of Crab Orchard. [16] In the first half of 1869, a school for freedmen was established at Shelby City (now part of Junction City), which was perhaps only two or three miles from where Stewart lived in June 1870.[17] In addition, by May 1869 the American Missionary Association operated schools for freedmen in Danville, South Danville, and Stanford. [18] Whenever Stewart was educated, he was fortunate to be able to read and write; by 1870 only 30% of Kentucky’s African-Americans aged 10-21 were literate [19].

Although the evidence is circumstantial, it is likely that in 1870 Robert Stewart met an early mentor/role model: William H. Gibson (1829-1906). Gibson was a free black man who moved to Louisville in 1847, where he became an educator. During the Civil War he recruited black soldiers for the Union Army in Kentucky and Indiana, and after the war he worked for the Freedmen’s Bank in Louisville. In 1867-68 he helped reorganize the United Brothers of Friendship (UBF), a black benevolent fraternal order in which he played a prominent role the rest of his life. In July 1870 Gibson was appointed by the Grant Administration as the first black U.S. mail agent in Kentucky, and in that position he served on the branch line of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad that ran through Stanford. As Gibson described in his 1897 autobiography, during his first two trips “the people at every station gathered by hundreds, and climbed upon the cars to get a view of the black animal who dared to invade their territory.” [20] It seems quite likely that Stewart met and spoke with Gibson during his six months on the Stanford line (In January 1871 Gibson was reassigned to the Louisville to Lexington route, and on his second day he was attacked by the Ku Klux Klan and nearly killed). Stewart later joined the UBF, which had a lodge in Stanford that Gibson visited c. 1875-76.

Robert Stewart married Louise Coffey, also a former slave, probably in December 1871 in Stanford, Lincoln County, Kentucky. It was there on December 7, 1871, that Robert and a friend, Smith Baughman, signed Robert and Louise’s Marriage Bond, which bound Stewart and Baughman to pay the Commonwealth of Kentucky $100 in the event the marriage did not take place. The Lincoln County court clerk wrote on the bond that Baughman had sworn he knew Louise’s mother and that she approved of the marriage, which likely occurred shortly after the bond was obtained. Stewart signed the document with an X, evidence that he was not yet fully literate.

Louise was born on July 20, 1851, probably in Monticello, Wayne County, Kentucky. Her mother was a slave named Polly Susebury (or possibly Suesbury; born c. 1832-35, died 1894). Louise’s father was her married white owner, Benjamin Franklin Coffey (1816-1868). Polly gave birth to two more of Coffey’s children, a girl in 1853 and a boy in 1855 or 56 (Coffey also had nine children by his wife, Mary Ann Worsham). The 1860 U. S. Census shows Benjamin Coffey owned 18 slaves who lived in five slave houses.

Beginning in 1858 Louise’s mother Polly had three children with Anderson Hickman, a free black man employed in the Coffey household as a blacksmith. Sometime in 1865 Polly, her children, and apparently Anderson Hickman moved north from Wayne County up to Lincoln County. However, in December 1865 Hickman seems to have married another woman, before his last child with Polly was born in March 1866. Probably in 1867 Polly married Alex Logan, a black laborer who in 1870 worked, along with Louise, for white farmer John G. Smith and his wife Nancy just northeast of Stanford in Lincoln County. Polly and Alex had children in 1868 and 1877, giving Louise a total of five half-siblings (not counting Benjamin Franklin Coffey’s nine white children) in addition to her sister and brother.

Robert William Stewart (often recorded as R. W.) and his wife Louise remained in Stanford, Lincoln County, Kentucky after their marriage. Their only child, William Malcom Edgar Stewart, was born there in August 1877 (probably on the 19th). When the 1880 U.S. Census was enumerated on June 2, Robert and Louise were living with their son in Stanford in the household of Horace S. Withers (1820-97), a widowed white farmer. Robert and Louise worked as servants for Withers and his two teenage children, James and Josephine. Although it is not known when the Stewarts started working for Withers, they were probably recommended to him by his niece, Nancy Smith, for whom Louise Stewart and her family had worked in 1870. The 1880 census also recorded that Robert could read and write, but Louise could not.

Compared to living in a more remote area of Lincoln County and working as a farmer or laborer, Stewart likely had more financial and physical security as Withers’ servant. However, Stewart was still a black man in the South, a point driven home in October 1879 when Stanford’s white Town Marshal, Smith Mershon, and two others broke up a United Brothers of Friendship meeting. At some point, Stewart must have become convinced that his family’s only chance to live a better life lay outside the South. In contrast, Robert’s parents lived out their lives in Lincoln County, and all his siblings lived all or most of their lives there as well.

Robert and his wife Louise likely disagreed regarding where they should move to. Louise’s mother Polly and all Louise’s siblings and half-siblings moved to Marshall County in northeast Kansas, c. 1878-1881, so that was surely Louise’s preferred destination. However, many press reports during that era describe black emigrants to Kansas as desperate and near starvation. Robert seemingly preferred the prospect of a relatively more predictable income from industrial work – about $2.00 a day – to life on a Kansas farm. Eventually the Stewarts left Kentucky and moved to Jeffersonville, Indiana, the closest city to Stanford north of the Ohio River (just over 100 miles away by railroad) and directly across the river from Louisville. For Robert, there were industrial jobs in Jeffersonville, as well as a UBF lodge, established in 1877. Louise could take some comfort in knowing that a good friend of her mother’s, Rebecca Cowan Coffey, lived with her family in Cheviot, Ohio, in 1880 a small town of 325 people near Cincinnati, about 140 miles up the Ohio River from Jeffersonville.

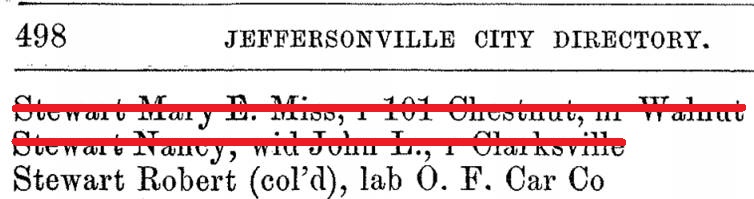

Exactly when Robert Stewart and his family left Stanford and arrived in Jeffersonville is not known, but it may have been in the summer of 1881, after his brother Harve’s July 28 wedding in Lincoln County, which Robert attended. He is not in the 1880-81 Jeffersonville City Directory, which was compiled and printed between May and July 1880. However, Robert Stewart is in the next Jeffersonville City Directory, which was canvassed from April to July 1882. He is listed as a laborer at the Ohio Falls Car Company (OFCC), which built railroad freight and passenger cars. In January 1881 the OFCC employed over 1,400 men, a figure that increased to 1,700 by July and to over 2,100 by January 1882.

However, the amount of work at the Ohio Falls Car Company fluctuated, as it did with other manufacturers in Jeffersonville. By April 1882 the OFCC was down to 1,500 workers, and near the end of May 1882 about a third of those were laid off. In October 1882 the company was down to 700 employees, with even fewer there over the winter before the OFCC’s workforce rebounded to 1,300 in April 1883. It is possible that Robert was laid off by the OFCC between the spring and early fall of 1882, was unable to find employment elsewhere in Jeffersonville, and was forced to find a job in Louisville, which had a population of over 120,000. The 1883 Louisville City Directory, compiled in the fall of 1882, lists Robert and Louisa Stewart (Louise’s name was sometimes recorded as Louisa) living together in a boarding house at 730 Ninth Street, just a block from Robert’s old Stanford friend Smith Baughman, who had moved to Louisville around 1875. The directory shows Robert as a laborer and Louisa as a domestic worker. If the Stewarts moved to Louisville in 1882, they probably returned to Jeffersonville before the fall of 1883, when the 1884 Louisville directory – in which they do not appear – was compiled.

While in Jeffersonville, Stewart met several men who would play important roles in his life; one of those men was future Los Angeles Chief of Police John Malcolm Glass. Born in Tennessee and raised there and in Alabama, Glass fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. He was demoted from sergeant to private due to cowardice at the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg, where he was captured and later paroled. He returned home to Alabama for about a month before he was ordered back into service. In November 1863 he deserted the Confederate Army in Tennessee and swore an oath of allegiance to the Union. He was next taken to Louisville, Kentucky, then released north of the Ohio River, likely at or near Jeffersonville. He later spent about five years as a guard at the Indiana State Prison South at Jeffersonville, ending in June 1876.

Unlike most Confederate veterans, after the war Glass was a Republican. Jeffersonville was primarily a Democratic town, but Glass won election twice as city marshal, serving from 1879-83. In May 1883 he began a single two-year term as Jeffersonville’s mayor after defeating five-term Democratic incumbent Luther Warder (who still has a park named after him in Jeffersonville). The Jeffersonville Daily Evening News carried many articles in the early 1880s that described the meetings of black Republican voters, and as Stewart was a Republican, he could easily have met Glass at a political event.

Stewart’s political activities in Jeffersonville apparently also led to his becoming acquainted with three other important local Republicans: shipbuilder David S. Barmore, his son Edmond H. Barmore, and their firm’s clerk/bookkeeper, Thomas J. Stuart. At some point after leaving the Ohio Falls Car Company – and possibly after living for about a year in Louisville – Robert Stewart began working at the Barmore Shipyard at the end of Meigs Avenue in Jeffersonville. Employment numbers at the yard fluctuated, but Barmore was reported to have between 250 and 300 workers from November 1882 to April 1883.

Stewart continued his membership with the United Brothers of Friendship during his years in Jeffersonville. In September 1885, the UBF’s Indiana State Grand Lodge met for its annual session in New Albany, Indiana (today about a 10-minute drive downriver from Jeffersonville), and an article in The New Albany Ledger from September 9, 1885, shows Stewart was not only one of three Jeffersonville delegates to the meeting, but he was also the outgoing state Grand Marshal.

While Stewart lived in Jeffersonville, he found employment, made political connections, and held important posts with his fraternal order, the UBF. However, his marriage seems to have become strained to the point that he and Louise separated. Perhaps one of the issues dividing them was that although Robert and Louise were both familiar with farm life and small towns (the population of Stanford, Kentucky in 1880 was about 1,200), Louise may not have adapted to living in Jeffersonville as easily as Robert did.

It is not known exactly when the Stewarts separated, but it was probably between sometime in 1883 and the summer of 1884. However Louise felt about Robert, her desire to leave Jeffersonville may have been hastened by either of two disasters. The Ohio River flood of February 1884 was the worst in recorded history up to that time, surpassing the previous mark set by the Ohio River flood of . . . February 1883. Both floods left almost all of Jeffersonville inundated and most of its residents homeless; food, clothing, and other supplies were sent by nearby towns and cities to relieve the suffering. Whenever Louise left Robert behind in Jeffersonville, she took their son William with her.

Louise probably went to live with her mother’s friend Rebecca Cowan Coffey in Cheviot, Ohio. Rebecca was born a slave in Kentucky a few years before Louise’s mother Polly. On the 1850 U.S. Census for Clinton County, Kentucky is a white man named John Cowan, born c. 1772. Immediately after him are listed 25 free black men, women, and children named Cowan – including Rebecca – strongly suggesting that, perhaps in the late 1840s, Cowan emancipated his slaves, some of whom he appears to have given or sold land to. The 1860 Census for Wayne County, Kentucky (adjoining Clinton County on the east) shows Rebecca Cowan living in the household next to that of Benjamin Franklin Coffey, whose slaves included Polly Susebury and her daughter Louise. Subsequent events show that Rebecca and Polly developed a close friendship during the years they were neighbors.

Rebecca married George Woodford Coffey (no relation to anyone else in this story named Coffey), a slave who ran away from his owner during the Civil War and joined the Union Army. By 1870 George and Rebecca Coffey were residing in Cheviot, Ohio. They remained there until moving in November 1884 – not to Missouri, where Rebecca’s sister lived – but instead to Marshall County, Kansas to live near Polly and her family. Louise probably moved to Kansas with the Coffeys at that time; the March 1, 1885, Kansas State Census shows Louise Stewart and her son William living in Frankfort, Marshall County, Kansas in a household that includes her mother and stepfather Polly and Alex Logan, their two children, and two of Louise’s other half-siblings, one of whom was Patrick Monroe Hickman. The census also shows that Louise and William came to Kansas from Ohio – not Indiana. Robert Stewart is not shown on that 1885 Kansas census because he was still in Jeffersonville.

We can only speculate as to how often Robert was able to visit his wife and son while he was in Jeffersonville and they were in Cheviot, Ohio. He may have traveled by steamboat to Cincinnati, then taken the narrow-gauge Cincinnati and Westwood Railroad, whose tracks ended in Cheviot. Regardless, it appears the Stewarts did not live together again until sometime in the second half of 1887, a separation of about three years. We must also speculate as to the effect this period had on young William Malcom Edgar Stewart, who grew up to be a very different person than his father.

Meanwhile, back in Jeffersonville during 1885, Robert Stewart’s world had begun to change. In April, Jeffersonville Mayor John M. Glass had decided not to run for reelection, and the Democrats recaptured the mayor’s office the next month. After Glass’ term ended he remained in Jeffersonville, active in business and in politics as a member of local and state Republican committees. However, perhaps already thinking of living elsewhere, he declined to run for Jeffersonville Township Trustee in March 1886.

Although the Barmore Shipyard had survived the floods of February 1883 and 1884 (reopening in April of both years), it did not survive two events that occurred in 1885, one of which was the fire that destroyed the yard’s sawmill on July 9. When the sawmill had burned down in 1877, the City of Jeffersonville loaned Barmore $10,000 to rebuild. Now, however, after the back-to-back floods it could not afford another loan. Nonetheless, newspaper articles from July to October 1885 indicated that Barmore would rebuild his shipyard. Robert Stewart may have assumed this would happen, perhaps encouraged by Barmore having completed several craft that were under construction at the time of the fire but had escaped the flames.

The other event that finally doomed the Barmore Shipyard was more protracted and less dramatic than the fire. Following the Ohio River floods of February 1883 and 1884, in July 1884 Congress passed – and President Chester A. Arthur signed – a Rivers and Harbors Appropriations bill that included $50,000 to build a levee to protect the U.S. Army’s Quartermaster Depot at Jeffersonville. The path of the proposed levee cut off access to Barmore’s property, leaving it impractical to build ships there. On September 17, 1885, David Barmore filed for an injunction to stop the levee construction next to his shipyard, and he was granted a temporary restraining order. However, on November 13, 1885, a circuit court judge ruled against Barmore and dissolved the restraining order. Barmore immediately sold his riverfront property and remaining supplies and machinery to the larger Howard Shipyard, located about 1/3 mile upriver.

By this time, David Barmore may already have decided to relocate to Los Angeles. His shipyard clerk/bookkeeper, Thomas J. Stuart, had visited Los Angeles in January 1885 and again in early November. On December 20, 1885, the Louisville Courier-Journal wrote that David Barmore had just returned from Los Angeles, where he and his son and their families would move in the spring. The Jeffersonville Daily Evening News reported on February 18, 1886, that David Barmore, his son Edmond, and Thomas Stuart and their families had departed Jeffersonville that day to relocate permanently in Los Angeles.

Consequently, by early 1886 Robert Stewart had to reevaluate his situation. He had lost his job at the Barmore shipyard after its sale. His former employer, the Ohio Falls Car Company, had shut down indefinitely in January 1885 (though it would finally begin to reopen at the end of July 1886). Stewart knew that in addition to the Barmore and Stuart families, other former Jeffersonville residents had moved to Los Angeles, and their reports of the area were all positive. At some point in early 1886, Stewart must have decided to leave Jeffersonville and relocate to Los Angeles. Lowered railroad fares, the result of transcontinental competition between the Southern Pacific and new rival Santa Fe, helped Stewart make the move.

Although we do not know when Stewart moved, there are clues. The February 9, 1886, Jeffersonville Daily Evening News, which listed R. W. Stewart as among those with a letter waiting at the post office, is the last indication we have of Robert Stewart in Jeffersonville. The postal laws and regulations then in effect regarding the advertising of letters waiting at a post office make it probable that Stewart had not yet departed Jeffersonville at that time. [e.g., Letters were not advertised if the postmaster knew the addressee regularly visited the post office, which Stewart may not have had reason to do since his wife, parents and most of his siblings could not write. Nor would Stewart’s letter have been advertised if he had left town and asked to have his mail forwarded to another post office, which postal rules allowed in 1886.] [23]

Stewart probably did not travel directly from Jeffersonville to Los Angeles. He may have first gone to Kentucky to visit his parents and siblings, and he must have stopped in Frankfort, Kansas to try to convince Louise to join him in moving to Los Angeles. This would likely have been the first time Stewart had seen his wife and son in at least a year and half, so he may have had an extended visit even though Louise decided to stay in Kansas.

Robert Stewart’s arrival in Los Angeles was probably in the spring or early summer of 1886. He is not listed in the Los Angeles city directory canvassed from early February to the first week of May 1886 and issued that June. If he arrived in Los Angeles before the first week of May 1886, he was missed by the canvassers and he failed to stop by the city directory company’s office to ensure his name appeared in their publication. However, depending on when Stewart left Jeffersonville and how long he stopped in Kansas, he may have arrived in Los Angeles after the directory went to press.

Whenever Robert Stewart arrived in Los Angeles, it was certainly no later than August 30, 1886, when he first registered to vote. His address and employer are not shown, but his occupation is listed as laborer. When Stewart relocated to Los Angeles, its black population was small but growing. According to the 1880 U.S. Census, just 102 of the 11,183 people living in the City of Los Angeles were black. By 1890, Los Angeles had 1,258 black residents, about 2.5% of its population of 50,395. [24]

Stewart appears in two Los Angeles city directories published in 1887 – one in May and another in August – living at 216 Castelar Street (now North Hill Street), just north of Alpine Street (known as Virgin Street until August 1887). The earlier directory indicates Stewart’s employer was the C. S. & A. & P. Transfer Company, a freight-hauling firm named for two railroads: the California Southern and the Atlantic and Pacific (both were part of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway system). Stewart worked not in the company’s main office but instead at the company’s stables, and he lived next door.

According to a Los Angeles city directory issued in June 1886, two of the C. S. & A. & P. Transfer Company’s three owners were Charles Elton, a former railroad engineer, and Edmond H. Barmore, newly arrived from Jeffersonville, Indiana. Both Elton and Barmore bought into the company in 1886, and by 1887 they were the only owners. Given Stewart’s prior work history with Barmore and his father in Jeffersonville, there seems to be little doubt that Edmond Barmore hired Robert Stewart to work at the C. S. & A. & P. Transfer Company. Records suggest that this occurred between September 1886 and early 1887.

Records also suggest that Robert was reunited with his wife Louise and son William around the summer of 1887. It is possible that Louise was persuaded to reconcile with her husband and move to Los Angeles by her half-brother, Patrick Monroe Hickman, who may have wanted to relocate there. Newspaper advertisements for Hickman’s nursery business in Frankfort, Kansas end in early May 1887, and the May 16, 1887, Los Angeles Herald lists Robert Steward (a common misspelling of Stewart) among those with a letter waiting at the post office – possibly the letter that told Stewart he would soon be joined by his family. Patrick Hickman probably accompanied Louise and William on the trip from Kansas to Los Angeles. Hickman appears on the Herald’s post office letter list as early as August 29, 1887.

The Los Angeles city directory canvassed in the spring of 1888 and issued that summer shows Robert Stewart (this time misspelled as Stuart) and Hickman both living at 243 Castelar Street, a home near the north end of the same block as Stewart’s previous residence at 216 Castelar. The same city directory also lists Stewart as a hostler for another freight-hauling firm named for a railroad, the S. P. (Southern Pacific) Transfer-Truck Company. This company had been purchased by David Barmore in October 1886, following his son Edmond’s becoming part-owner of the C. S. & A. & P. Transfer Company earlier that year.

Stewart’s move from 216 to 243 Castelar, probably sometime between the summer or fall of 1887 and the spring of 1888, may have coincided with his change in employer, because 216 Castelar seems to have been owned by the C. S. & A. & P. Transfer Company as housing for its workers at its adjacent stable. As to why Stewart changed employers, perhaps it was because he wanted a better home for his family: 216 Castelar was older and surrounded on two sides by a stable and corral. It is also possible Stewart did not get along with Edmond Barmore’s partner, Charles Elton. Stewart lived at 243 Castelar until approximately late 1888 or early 1889.

Directly across the street from 243 Castelar was the Castelar Street School, which 10-year-old William M. E. Stewart likely began attending in the fall of 1887. The school had only four rooms but 198 desks, and due to overcrowding it was on double sessions, with students attending class for about four hours a day. When William lived in Indiana and Ohio, the public schools there were segregated. In Los Angeles, the public schools had been integrated since the city’s “Colored School” was discontinued in 1881. However, the 1887-88 Los Angeles school census recorded just 261 black children aged 5-17, compared to 10,360 white children [25]. In the fall of 1887 William should have been old enough to start the fifth grade, assuming his prior education had kept him at grade level. After the sixth grade, William would have attended seventh and eighth grades at Sand Street School on Fort Moore Hill (this school was the renamed old Los Angeles High School building, opened in 1873 and laboriously relocated in 1886 to make way for a new Los Angeles County Courthouse). We do not know how long William stayed in school, other than he did not graduate from L.A. High School. However, we know that as a teenager he worked at a grocery store on the northwest corner of Buena Vista (now North Broadway) and Alpine Streets.

Probably between the fall of 1888 and early 1889, Stewart and his wife and son moved two blocks east and one block south to 767 New High Street, on the southwest corner of Alpine Street. North across Alpine was the S. P. Transfer Company stable where Stewart worked c. 1887-88 to 1889. His next move, probably between April 1891 and March 1892, was just around the block to 764 Buena Vista Street, his fourth known Los Angeles residence.

It was at the S. P. Transfer Company that Stewart may have reconnected with future Los Angeles Police Chief John M. Glass, who later would be instrumental in prolonging Stewart’s LAPD career. Glass had not moved to Los Angeles in February 1886 with the Barmores and Thomas Stuart, but in August and September 1886 Glass toured the west coast, including an extended stop in Los Angeles with the Barmores. Glass was apparently anxious to return – perhaps to get in on the real estate boom then underway in Los Angeles – because the Jeffersonville Daily Evening News reported that Glass would leave town on October 17, 1886, to relocate to Los Angeles. At the end of November 1886, Thomas Stuart traveled back to Jeffersonville to bring Glass’s family to L.A.

Glass is listed in the Los Angeles city directory issued in May 1887 as working for the Southern Pacific Transfer Company, no doubt hired by his old Jeffersonville friend David Barmore before he sold the company in July 1887. Given that Robert Stewart likely switched employers between the summer of 1887 and the spring of 1888, he may have been hired at the Southern Pacific Transfer Company by either David Barmore or by the company’s new owners on the recommendation of John M. Glass. The 1888 city directory lists Glass’ occupation as “Real Estate.” In April 1888 Glass won election as a delegate to the Los Angeles County Republican Convention. Despite his political affiliation, Glass was appointed to the Los Angeles Police Department as a detective in 1888 – apparently in October – during the administration of Democratic Mayor William H. Workman.

Robert William Stewart also participated in local Republican politics. A meeting to form a “Colored Republican Club” (CRC) occurred on June 4, 1886, possibly just before Stewart arrived in L.A. However, Stewart may have attended the CRC gathering on August 20, 1886 (he registered to vote 10 days later). Another CRC meeting, attended by both white and black Republicans, was held on the night of October 14, 1886, and Robert William Stewart was among those who addressed the crowd:

The “Colored Republican Club” in Los Angeles dissolved after the 1886 elections. There was no attempt to revive it until a meeting on January 18, 1888, which was chaired by black journalist and attorney R. C. O. (Robert Charles O’Hara) Benjamin, who had arrived in L.A. around October 1887. Benjamin believed that African-Americans held the balance of power between the two major political parties, so the black community should “be strictly independent of both Republicans and Democrats,” leaving black voters free “to support any measure by which they would be gainers, whether fathered by the Republican or Democratic party.” [26] However, that initial meeting attracted just 14 people, and a follow-up meeting a week later was canceled when it drew only half that number.

It was not until April 21, 1888, that a new “Los Angeles City and County Colored Republican Club” was formally organized. The club’s officers included African-Amercans who were staunchly Republican as well as others who were “independents” like R. C. O. Benjamin and Thomas Pearson, who came down to L.A. from Oakland the previous year and became aligned with Benjamin. The club passed a resolution that read, “the interest of the colored citizens of this city and county will be better served by working in conjunction and harmony with the white Republicans . . . we pledge ourselves to give them our undivided support.” [27]

Nonetheless, unlike in 1886 when Los Angeles had a single “Colored Republican Club,” in 1888 L.A.’s black community split between solid Republicans like Robert Stewart and the independents who sided with Benjamin and Pearson. Many independents supported the national GOP ticket, but at the state and local levels were open to voting for Democrats. Campaign clubs were formed by voters on both sides of the political divide, which was represented by two black-run newspapers in Los Angeles.

On July 7, 1888, the first edition of the Weekly Observer appeared, [28] edited by R. C. O. Benjamin. Despite Benjamin’s comments in January about black political independence, his Weekly Observer was initially believed to be a typical pro-GOP organ. However, on August 6, 1888, the Los Angeles Herald reprinted the Weekly Observer’s praise for the independents: “judging from the number of Negro independent clubs that are being organized . . . the death knell of the Republican party will be sounded unless they change their tactics toward the Negro. A great many white Republicans have an idea that the Negro owes the party a debt of gratitude, and it is therefor [sic] his imperative duty to vote the [Republican] ticket no matter if a dog is placed on it.” Also on August 6, the Herald quoted the Observer’s criticism of a GOP candidate for superior court judge in L.A. County. Benjamin’s Weekly Observer went on to attack other Republican candidates, the L.A. County GOP Central Committee, and several black Los Angeles residents, including Robert Curry Owens (grandson of African-American Los Angeles pioneer Biddy Mason), who on September 8 tracked down Benjamin and punched him in the jaw.

In addition, on September 4 the Los Angeles Times reported that Benjamin’s associate Thomas Pearson had helped organize the “Colored Men’s Republican Protective League” (CMRPL), a group of independent black voters that resolved to “support only such men as will advance the material interests of our country in general and advance the political interests of our race in particular.” On October 27, the Los Angeles Herald called Pearson “the prime mover in the independent movement which started in this city eight weeks ago.”

To oppose Benjamin and the Weekly Observer, in early September 1888 another group of black Republicans – which included Robert Curry Owens – began a newspaper that consistently supported the GOP, the Republican Advocate. [29] It was edited by one of its founders, John J. Neimore, who subsequently helped to shape the course of Robert Stewart’s life.

Stewart was not an independent; his views were closer to Neimore’s. Stewart saw no place for African-Americans outside of the GOP, nor did his brother-in-law, Patrick Monroe Hickman. Together, Stewart and Hickman attacked the Weekly Observer’s R. C. O. Benjamin and Thomas Pearson in the following letter, published in the September 15, 1888, Los Angeles Times:

The election for federal, state, and county offices on November 3, 1888, produced Republican majorities in Los Angeles County for all GOP candidates, despite Thomas Pearson’s group of independent black voters endorsing four Democrats for L.A. County offices. [30] The GOP did not do as well in the Los Angeles City election of December 3, 1888. Democrat John Bryson won the mayor’s race by 941 votes out of 9,835 cast. The split in the black vote was just one factor in the election, but Bryson had been backed by the “Independent Republican Colored Club” (possibly the same group as Pearson’s CMRPL) and the “Bryson Colored Club.” In addition, the Democrats captured five of the eight City Council seats that were contested, giving the Democrats an 11-4 council majority.

Mayor Bryson was inaugurated on December 17, 1888. On December 21, the Los Angeles Evening Express published an article that said it was “generally understood that Mayor Bryson was about to appoint two colored policemen.” On December 22, the Evening Express ran this short item:

Two days later, the Evening Express addressed the threatened police resignations in an editorial. It said any white officers who resigned because black officers had been appointed “would merit and . . . receive the contempt of the community,” but the Evening Express stopped short of advocating for black officers on the LAPD:

During this era, all of L.A.’s police officers were appointed or reappointed each year by the Police Commission. When the LAPD’s roster for the ensuing year was revealed on December 31, 1888, it did not include any black officers (it did, however, include Mayor Bryson’s son). The threats of white LAPD officers to resign may have stopped Bryson from ensuring two black officers were named to the force. Another reason may have been that one of the two purported leading African-American applicants was discovered to be a bigamist and fled to Mexico to avoid prosecution. [31]

Los Angeles’ new city charter, which took effect in January 1889, prompted another city election, which occurred on February 21, 1889. In the lead-up to this contest, L.A.’s African-American community was more unified, with no proliferation of opposing political clubs. Perhaps the independents and the regular Republicans “agreed to disagree” about certain issues, and the city’s white GOP establishment may have tried to heal the breach among its black supporters.

Mayor Bryson, elected just two and a half months earlier, ran for reelection on February 21, but this time the vote was an overwhelming GOP victory. Republicans won all eleven citywide offices, led by Henry T. Hazard, who defeated Bryson for mayor by over 2,300 votes. Republicans also won all the city council seats (there were now nine instead of 15) and eight of nine seats on the Board of Education. The GOP had gained control of city government with the assistance of L.A.’s black community, which wanted their help to be acknowledged and repaid.

The new city charter expanded the Police Commission from three members (the mayor, chief of police, and city council president) to five (the mayor and four appointees – no more than two from the same political party – approved by the city council). On March 23, 1889, the new Police Commission named James F. Burns Chief of Police by a 3-2 vote.

The new Police Commission also set out to reorganize the LAPD, and this was a highly politicized process. At the Police Commission meeting of March 30, 1889, after the names of 277 applicants had been read, a new police roster, approved by Chief Burns, was finalized. When the names of the officers were announced, they were divided into Democrats and Republicans. Among the new Republican officers were Joseph Henry Green and Robert William Stewart, whose appointments must have resulted from pressure applied by leaders of the black Republican community (like newspaper editor John J. Neimore) on local white Republican leaders, who in turn leaned on the City Council and Police Commission. A subsequent article in the Los Angeles Record asserted that banker George Bonebrake (1837-1898) used his influence to get Stewart appointed, as did Stewart’s old shipyard and transfer company boss, Edmond Barmore.

At the Police Commission meeting on April 1, 1889, there was at least one reaction to Stewart and Green joining the force. The commissioners voted to allow anyone who had an application on file to join the LAPD to withdraw that application. Left unsaid was why this was an issue, although whites not wanting to join a police department that now employed black officers is a safe guess.

In April 1889 three LAPD officers quit, but it cannot be confirmed that they did so because the department hired two black officers. On April 1, the Police Commission accepted the resignation of Peter Alexander Reel, a four-year LAPD veteran. On April 2, Reel was appointed a Los Angeles County Deputy Sheriff. The timing of Reel’s job switch is curious, but the change would have taken time to arrange and could be a coincidence. Next to go was Officer Jeremiah J. Camozzi, whose resignation was accepted on April 10. Known as “Jerry Comocy,” he was appointed to the LAPD in January 1887 but never sworn in due to questions about his character. He got on the force in February 1888 but that October was dismissed for cause. Incredibly, he was reappointed in January 1889 and again on March 30. At the time he quit he was divorcing his wife, who said he was a violent drunk who beat her and assaulted her 11-year-old sister. The third officer to resign from the LAPD in April was Albert Lincoln Smith, who quit on the 16th. Before he was named to the LAPD on March 30 he had been a Deputy Constable under his brother, Los Angeles County Constable Fred Smith. Why Albert L. Smith soured on the LAPD after just 17 days is unknown, but by June 1889 he was back working for his brother as a Deputy Constable and in April 1891 joined the Los Angeles Fire Department.

Currently archived Los Angeles newspapers from the first two months after Stewart and Green joined the LAPD do not mention either their race or any public dissatisfaction with their status as police officers. Also absent are any reports of what kind of reception Stewart and Green received from their brother officers. It may well have been awkward and not especially warm. However, L.A.’s two black policemen – and the reaction to their appointment – quickly made news in the state capital:

Although the Record-Union wrote that Stewart and Green “went on duty,” they apparently were not immediately given the same assignments as other officers. Chief Burns may have accepted two African-Americans on the force as necessary because of political considerations, but he seems to have initially resisted using Stewart and Green to protect Los Angeles residents:

|

| April 3, 1889, Los Angeles Times. G. H. Baxter was an African-American resident of Los Angeles who worked as a porter and janitor. |

Burns soon relented, and Sacramento’s Daily Record-Union updated its readers on the situation in Los Angeles. The newspaper again misspelled Stewart’s name but probably did not err in its description of the crowd’s reaction to the sight of a black man in a police uniform:

Los Angeles’ two black police officers were also news in San Francisco. We know from voter registers that Joseph Green’s height was about 5 feet 7 inches, and since the article below also refers to a “six-foot negro,” Robert Stewart must be the one whose speech is mocked.

On April 11, 1889, when the LAPD was reduced from 100 to 90 men, both Stewart and Green had passed their physical examinations and were officially confirmed as permanent members of the force. Stewart was classified as a foot patrolman, a position that paid $80 a month. One of his first arrests may have been on April 23, when he detained a man the Los Angeles Times identified as W. H. Braun for an unspecified misdemeanor. Both Stewart’s race and his size made an impression. A June 13, 1889, Times article told how Stewart, “the big colored policeman,” arrested two men for fighting, and on August 4, 1889, the Los Angeles Herald, in describing the court appearance of an unruly drunk, called Stewart “the colored giant in blue.” Voter registers of the 1890s list Stewart as being 6 feet 1-1/4 inches tall. The registers also show Stewart as having two identifying scars on his left hand, but how he got them remains a mystery.

On July 17, 1889, the Police Commission voted to dismiss James F. Burns as Chief of Police and named John M. Glass to succeed him, with Glass officially taking over on July 24. In February 1890, the Mayor and City Council ordered the size of the LAPD be further reduced to a total of 80 (excluding the Chief and Matron). Of these, 68 were foot patrolmen, whose salary was cut $10 to $70 per month. To pare down the force, on February 17, 1890, the Police Commission asked Chief Glass to produce a list of 15 officers from which the commissioners would select nine officers to be removed. Joseph Green was among the nine, leaving Robert Stewart as the sole African-American with the LAPD. Only three surviving newspaper articles from 1889 mention Officer Green’s police work (arresting a drunk in September and answering the phone at Police Headquarters on Christmas Eve), compared to at least 14 articles that refer to Stewart over the same period.

Newspaperman John J. Neimore (who had published the Republican Advocate during the 1888 elections) presented that resolution at the GOP convention’s first night, September 6, at Turnverein Hall on Spring Street. His remarks to the delegates, which included a warning that African-Americans would not vote the Republican ticket unless they were represented on it, “were both applauded and hissed,” according to the Herald.

Vignes then removed his name from consideration, implying impropriety in the proceedings, although he still received some votes. The results of the second ballot showed Stewart had received 99 votes and none of the other candidates more than 19. Stewart was then declared the unanimous choice of the convention. As Republican nominee for Los Angeles Township Constable, Robert Stewart was the first African-American to be nominated by a major party for an elective office in Los Angeles County. [The Prohibition Party had broken the color line in 1888 by nominating African-American Shadrach Bristow Bows, also for Los Angeles Township Constable. [41] Bows (c. 1840-1902), born in Kentucky and educated at Oberlin College in Ohio, worked in Los Angeles as a carpenter.]

When Stewart returned to the force in January 1893, L.A.’s population was around 70,000. At this time the LAPD had just 74 officers (including the Chief and Matron); of these, only 49 were foot patrolmen, three of whom were stationed at busy intersections to direct traffic. The salary of a foot patrolman was $70 a month, unchanged since February 1890 (for comparison, in January 1893 San Francisco’s estimated population of 350,000 was protected by a police force with an authorized strength of 456; of these, 384 were patrolmen, who earned $102 a month) [44]. Although all members of the LAPD had a paid 10-day annual summer vacation, the rest of the year they worked eight hours a day, seven days a week [45]. Officers were expected to testify at court proceedings on their own time if the proceedings were held when the officers were not on duty. In addition, while the foot patrolman’s salary was raised to $83.33 a month in September 1894 (with $2 withheld from each officer’s check and paid into a police pension fund), mandatory, unpaid overtime was common.

During 1893 and 1894, newspaper articles describe Stewart finding dead bodies, bringing insane people to Police Headquarters, and of course making arrests, like this one:

Robert and Louise were joined in their 1895 relocation to Elmore/Ceres Avenue by Louise’s half-brother Patrick Hickman. Hickman moved into a house that would eventually become 753 Ceres Avenue, across the street and north two houses from Robert and Louise’s new residence. After arriving in Los Angeles in 1887, Hickman first worked as a teamster and hostler. Then c. 1892-98 he was County Courthouse janitor and City Hall janitor/watchman, positions to which he was appointed through political patronage.

Robert and Louise’s 17-year-old son William seems to have moved out of his parents’ new home shortly after they moved in. After working at the grocery store at Buena Vista and Alpine Streets, by November 1894 he was employed as a porter at W. S. Allen’s furniture and carpet store on South Spring Street. The 1895 Los Angeles City Directory lists William twice: as a porter living at 762 Elmore, and as a porter for W. S. Allen and living at 804 E. First Street. The double listing probably occurred because William moved in the spring of 1895 during the directory’s canvass, and his original information was not removed when he provided his updated address. The 1896 directory shows William back living with his parents and with no occupation listed. On October 3, 1896, the Los Angeles Herald reported that two young black men had been arrested for drunkenness the previous morning, one of whom “proclaimed himself the son of Robert W. Stewart, the only colored police officer on the force.” Although both men were booked at Police Headquarters and locked up, no complaint was filed against William, and he was allowed to go home when he sobered up (the article identifies him as William H. Stewart, not William M. E., but presumably he was recognized as Robert’s son). The 1897 city directory still has William living with his parents but working as the assistant janitor at the Los Angeles Theatre on South Spring Street. William may have then left Los Angeles, as there is no record of his whereabouts in 1898 or 1899.

On November 19, 1895, Sam Haskins, the first African-American hired by the Los Angeles Fire Department (on June 1, 1892), also became the first Los Angeles firefighter to die in the line of duty. While responding to a fire, he fell off a steam engine and was crushed between one of its wheels and its boiler. On November 22, Stewart was one of Haskins’ pallbearers at his funeral at Evergreen Cemetery in East Los Angeles (although the Fire Commission authorized $70 to cover the cost of Haskins’ funeral, his grave would be unmarked for over 100 years). Another pallbearer was fireman Albert L. Smith, who had quit the LAPD in April 1889 just 17 days after he and Stewart were appointed (Smith rejoined the LAPD in 1898 and served until 1921). A week after Haskins’ funeral, Stewart had this disheartening experience:

In 1896 Stewart suffered from ill health, described in the press as rheumatism. He was paid his regular $83.33 foot patrolman’s salary for January, but then his illness began to keep him at home. He worked only 14 days in February, earning $40.22, and for March he was paid $45.24. For April he received $41.66, a half-pay disability payment that indicates he did not work at all that month.

On July 23, 1896, Stewart almost exhausted himself helping to subdue a man gone berserk after receiving cocaine to dull the pain of a tooth extraction. In August, Stewart celebrated with the rest of the LAPD as their Headquarters was relocated from a cramped, smelly building on the north side of Second Street between Spring and Broadway to a new structure on the south side of First Street between Broadway and Hill. That November, Stewart and his chickens were in the news again:

While Stewart was struggling with rheumatism from February to June 1896, he received only 52.8% of the salary he would have been paid had he not missed any days. This led to a series of financial problems for Stewart. To begin with, Stewart found himself on the Los Angeles City Tax and License Collector’s delinquent list in June 1896 (for the 1895-1896 tax year), owing $1.38 on a $595 mortgage with the Columbia Building and Loan Association (likely for his new home), plus personal property. Stewart made the city delinquent tax list again in July 1897, owing $1.35 on his now $580 mortgage. Distressingly, Stewart had also been on the state and county delinquent tax list in June 1897, owing $.89 for personal property and $4.50 for a poll tax ($1 in 1897 = ~$32 in 2021 [48]).

Stewart’s personal financial problems also affected him professionally. In November 1896, the Police Commission received a complaint from the owner of a clothing store that Stewart owed $18 but refused to pay. The matter was referred to Chief Glass and seems to not have appeared in the press again; presumably the debt was legitimate and Stewart paid the $18. In April 1897, after hearing a complaint that Stewart would not pay $26 he owed to a different clothing store, the Police Commission ordered Stewart to pay the amount owed in 10 days or he would be dropped from the force. He was also fined 10 days’ salary. August 1897 saw the owners of a hardware store tell the commission Stewart owed them $13.75 they could not collect. In both 1897 cases, Stewart paid the amounts due. However, the Police Commission received more complaints about Stewart owing money in 1898 ($2) and 1899 ($18.50). Again, Stewart paid both debts, but these incidents may have strained his relationship with Chief Glass.

As far as his police work in 1897 was concerned, as usual he was mentioned in several newspaper articles for making arrests. One of those was of Martin Biscailuz, father of future Los Angeles County Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz, for stealing law books from an office. That June, at age 47, Stewart performed a feat of remarkable strength and courage. A newspaper article described the incident and commended him, though not without needlessly mentioning his race and using the words Darktown, dusky, and Ethiopian:

Stewart continued to be the LAPD’s only black officer until June 30, 1897, when Berry Richard Randolph was appointed as a special officer to replace regular officers who were taking their summer vacation. Randolph did well and was made a permanent officer on September 29, 1897. The LAPD had not had two black officers serving simultaneously since February 1890, when Joseph Green was fired. Randolph, who had originally applied to the LAPD in December 1894, was on the force for eight and a half years.

From 1898 through the first part of May 1900 Stewart continued as a patrolman. He performed such routine duties as making arrests, testifying in court, finding lost children, and taking injured people to the Receiving Hospital at Police Headquarters, where he also served as acting jailer. On May 16, 1899, when the LAPD replaced its officers’ old eight-point badge (or “star”) with a six-point badge, Stewart received badge #40. The numbers were assigned according to length of service with the department, placing Stewart 40th in seniority. It is unclear whether his seniority was determined using all his years of service (including 1889-92), or if it was based on when he returned to the department in January 1893.

The year 1900 did not begin well for Robert Stewart and his family. On December 26, 1899, LAPD Chief John M. Glass resigned, effective immediately, after losing a two-month power struggle with the City Council. Stewart had known Glass since the mid-1880s back in Jeffersonville, and their relationship no doubt had helped protect Stewart’s position with the LAPD. [On October 31, 1899, the Police Commission had approved by a 3 to 2 vote Chief Glass’ plan to increase the department’s efficiency by demoting eight officers and promoting others to replace them. Most of the demoted officers – especially Captain William Roberts – were well-connected politically, and on November 1 the City Council responded by voting 5 to 3 to declare the Police Commission vacant (except for Mayor Eaton, whom they could not remove from the commission). Soon after, the City Council named a new Police Commission with four members who opposed Chief Glass and planned to remove him from office; among the new commissioners were Robert Ling and William Scarborough. Mayor Eaton and the other two members of the “old” commission who supported Glass’ plan continued to assert they were the official commission. This left the city with two Police Commissions claiming to hold authority. City Attorney Walter F. Haas issued an opinion on November 13 stating the old commission was in charge until it was removed by a judicial decree, obtained only through quo warranto proceedings that had to be authorized by the state attorney general. On November 14, the new Police Commission voted to begin the quo warranto proceedings, which California Attorney General Tirey Ford authorized on December 7. The legal outlook for the old commission was bleak after their attorneys failed to delay the lawsuit on December 22, and this led to Chief Glass on December 26 submitting his resignation to the old commission, which also resigned the same day, ending the standoff. The next day, the new Police Commission reversed all of Glass’ personnel demotions and promotions and named Captain William Roberts – who Glass had demoted to sergeant – the acting chief.]

Then at 7:45 p.m. on Thursday, May 10, 1900, Robert William Stewart’s life changed forever. While he was at Police Headquarters preparing to go out and walk his beat, he was arrested by LAPD Detectives Jason J. Hawley and Walter H. Auble and locked up on a charge of rape. Stewart was accused of assaulting a 15-year-old white girl named Grace Cunningham the previous night at around midnight while he was on duty.

Near midnight at the corner of Sixth and Broadway she met Stewart, who asked her name, where she lived, and why she was out so late. She said Stewart offered to walk home with her, but when they arrived at her house he did not believe she lived there, and he told her to walk with him. Back over on Broadway, Stewart asked her to step inside a partially completed building with him, but she refused. Then another police officer walked by, and Stewart stepped back out of the light and told her to go home. At that point she said she demanded to be taken home. Stewart agreed and suggested they take a short cut through the grounds of the nearby Spring Street School. That was when, she claimed, he pushed her onto the steps on the north side of the school building and raped her. After Stewart left, she ran home and told her mother what had happened.

Stewart proclaimed his innocence. He admitted meeting her on Broadway between Fifth and Sixth Streets at about 11:00 p.m., but he said he did not know her name or what she looked like and would not be able to recognize her if he saw her again. He denied touching her or even walking with her.

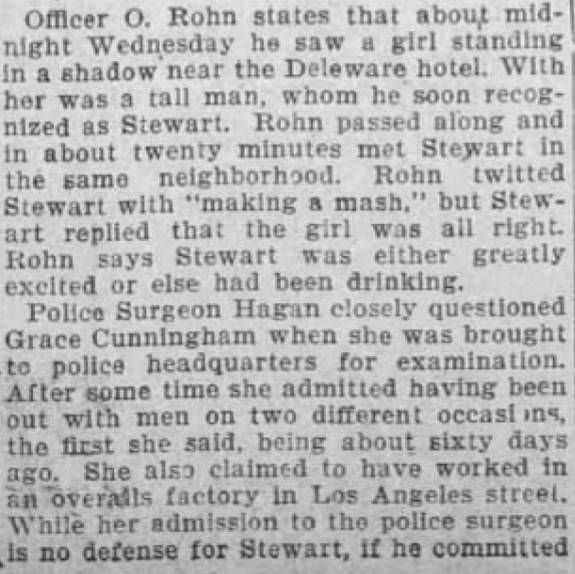

LAPD Officer Orlando Rohn said he had seen Stewart talking with a girl on Broadway at about 12:30 a.m. When Stewart joined him at a tamale stand about 20 minutes later, he joked with Stewart about the girl, but Stewart dismissed Rohn’s insinuations. Rohn also said he thought Stewart had been drinking.

Stewart received more bad news on May 19: he was being

sued. Back in October 1898, a cement contractor named George Banaz had won a city contract to construct a sewer on Stewart’s block of Ceres Avenue. The property owners had to pay an assessment to Banaz for building the sewer, which was completed in January 1899. Banaz alleged that Stewart never paid any part of the $15.20 assessment he owed. This is plausible, given the financial trouble Stewart seems to have been experiencing at the time. Banaz had filed his suit in Los Angeles County Superior Court on May 11, 1900; reading about Stewart’s arrest the day before apparently jogged Banaz’ memory. He sued Stewart for the $15.20, plus 10% interest per year from January 27, 1899. If Stewart lost he would also have to pay the $15 filing fee earned by Banaz’ attorney. Stewart had 10 days from the date he was served, May 19, to respond to the suit. [On May 11, Banaz also sued Mary Bronson, who lived just two homes south of Stewart on Ceres Avenue, for an unpaid sewer assessment. However, she received her summons on May 17, two days before Stewart received his, suggesting Stewart was not at home on May 17 and could not immediately be located. This is possibly because he was being hidden to ensure he was not lynched, an all-too-common fate of African-American men accused of rape in this era.]

Numerous newspaper articles from 1889-92 describe Stewart making arrests for such crimes as assault with a deadly weapon, battery, robbery, disturbing the peace, and larceny. He also testified in court and helped people who needed medical treatment. Some incidents he responded to were equine-related. While he was off-duty on August 7, 1890, a runaway horse caused a carriage to overturn near his home; Stewart rushed out to assist the two people injured and help right and repair their carriage. On September 15, 1890, Stewart witnessed an accident that severely injured a horse, and on the advice of a veterinarian, Stewart ended the horse’s suffering by shooting it.

A particularly memorable day for Stewart must have been April 22, 1891, when President Benjamin Harrison visited Los Angeles, just the second time a U.S. President had been to the city. Stewart was not among the 20 LAPD officers (four mounted and 16 marching with rifles) who were at the front of the presidential parade. However, Chief Glass ordered the entire force to work the event, so Stewart was almost certainly among the officers used to keep the streets clear. A crowd estimated as high as 60,000 watched the President’s procession, which began a little after 3:00 p.m. at the Southern Pacific Railroad depot at Fifth Street and Central Avenue. The parade ended at City Hall, which was then on the east side of Broadway, just south of Second Street.

From December 7-11, 1891, the 221-pound Stewart was a member of the LAPD tug-of-war team, which competed against five other local teams before packed crowds of around 4,000 people in L.A.’s Hazard’s Pavilion. The tug-of-war contest was organized and sponsored by the Los Angeles Athletic Club following a similar event in San Francisco. The November 24, 1891, Los Angeles Evening Express noted that proceeds from the contest would be used to complete construction of Athletic Park (on the northeast corner of 7th and Alameda Streets, Athletic Park was L.A.’s primary outdoor sports venue c. 1892-97). On the eve of the tournament, the December 6 Los Angeles Times alluded to Stewart’s presence by advising its readers that in the LAPD's opening contest, “a first-class dark horse will be trotted out before the public.”

The police lost their first four matches. The first contest went on for an hour and 26 minutes, but in two subsequent matches the police were dispatched in less than a minute. The LAPD won their final contest, with Stewart and a teammate straining so hard during the 24-minute match that they fainted right after the victory and had to be carried off. The LAPD team’s captain, William C. Roberts, whose strategy in the first tug was criticized in the press (inexplicably, he had the team ease up and rest when it had momentum and was on the verge of victory), made the dubious claim that four of his team, including Stewart, had been ill during the week and thus not at their best. The tournament’s winning team was assembled by its non-tugging captain, Edmond Barmore, and one of its members was 203-pound Charles Elton.

The police lost their first four matches. The first contest went on for an hour and 26 minutes, but in two subsequent matches the police were dispatched in less than a minute. The LAPD won their final contest, with Stewart and a teammate straining so hard during the 24-minute match that they fainted right after the victory and had to be carried off. The LAPD team’s captain, William C. Roberts, whose strategy in the first tug was criticized in the press (inexplicably, he had the team ease up and rest when it had momentum and was on the verge of victory), made the dubious claim that four of his team, including Stewart, had been ill during the week and thus not at their best. The tournament’s winning team was assembled by its non-tugging captain, Edmond Barmore, and one of its members was 203-pound Charles Elton.

Stewart was also mentioned in a short Herald article on April 23, 1892, that described a hen he owned. It was notable because it laid two eggs each morning, every day; the first at around 6:00 a.m., and the second about four hours later. Raising chickens was a hobby of Stewart’s, as was his membership in fraternal orders. Although the July 10, 1888, Los Angeles Evening Express noted that L.A. had a 35-member-strong lodge of the United Brothers of Friendship (UBF), which Stewart belonged to in Kentucky and Indiana, he does not seem to have joined the UBF in Los Angeles.

Instead, Stewart was active in the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (GUOOF), said by the same July 10, 1888, Evening Express article to be “the most substantial” of the local black community’s secret societies with 65 members. Probably not long after he arrived in town in 1886 Stewart joined Los Angeles GUOOF Lodge # 2639, which had been formally established in June 1885 [37]. Stewart was well-received by the members of Lodge # 2639 and had already served a term as its highest officer, Noble Father, by October 1891. His brother-in-law, Patrick Hickman, also joined the lodge.

Stewart had been named to statewide positions in the UBF, and he was likewise honored by his fellow GUOOF members. At an August 1894 convention in Los Angeles, Stewart was appointed Grand Marshal for GUOOF District Grand Lodge #32, which was comprised of all the individual GUOOF lodges in California. Stewart also helped to start a second GUOOF lodge in Los Angeles in 1904. [The all-white Independent Order of Odd Fellows would not admit black Americans, but in 1843 the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in England began authorizing new lodges for African-Americans (though the lodges were open to all races), and by 1896 the GUOOF claimed over 100,000 active members in the U.S.] [38]

Robert Stewart had been a trailblazer as a black LAPD officer in 1889, and he achieved another first with his participation in local Republican politics in 1892. At the time, Los Angeles County government was divided into townships (e.g., Los Angeles, Long Beach, Pasadena, Santa Monica, Cahuenga, Ballona), with each having law enforcement officers called constables. Los Angeles Township had two constable positions, so the Democrats and Republicans each could run two men for the posts in the November 8, 1892, election. The GOP’s nominees for all the county offices would be selected at the Los Angeles County Republican Convention, set to begin September 6, 1892.

On the evening of September 5, the Colored Republican Club

met and adopted a resolution, part of which stated, “It is with shame and

sorrow we point to the fact that the only office, federal, state or local,

which the Republican party has heretofore conferred on a colored man in Los

Angeles County has been that of janitor.”

The resolution concluded, “That because we are a law-abiding,

industrious and tax-paying body of citizens, and not moved hereto by a mere

lust for office, but by a decent respect for the dignity of our race, that we

demand from the Republican party of Los Angeles county representation on the

county ticket, and that we demand two places thereon, as entitled by our

numerical strength.”

Newspaperman John J. Neimore (who had published the Republican Advocate during the 1888 elections) presented that resolution at the GOP convention’s first night, September 6, at Turnverein Hall on Spring Street. His remarks to the delegates, which included a warning that African-Americans would not vote the Republican ticket unless they were represented on it, “were both applauded and hissed,” according to the Herald.

|

| The 1892 Los Angeles County Republican Convention was held at Turnverein Hall, 231 S. Spring Street. This photo of that building (with MUSIC HALL at the top) was taken in 1895. |

By September 1892, Robert Stewart had been in Los Angeles

for over six years, on the police force for over three years, was well regarded, and he was a solid

Republican. Consequently, Neimore and

other Republican leaders of the Los Angeles African-American community decided on Stewart as their candidate for county office.

The Herald reported on

September 9 that they “will demand for him the nomination for [Los Angeles Township] constable.” In 1890 Robert Curry Owens, one of L.A.’s most prominent African-Americans, had tried but failed to get the GOP nomination for the same office.

Near the end of the county GOP convention on September 9, 1892, the

last office for which nominees were chosen was Los Angeles Township

Constable (Los Angeles Township was the city of Los Angeles plus the nearby communities of Burbank, Garvanza, Glendale, and La Crescenta). A white attorney named William

T. Williams placed Stewart’s name in nomination and gave a speech commending

him. Williams next offered a motion to

nominate Stewart by acclamation, but it lost.

Five white men were then nominated, including incumbent Lester D.

Rogers, one of two Republicans elected Los Angeles Township Constable in 1890,

and A. C. Vignes, a former L.A. policeman whose family had been in town for 60 years. He was now a streetcar operator and a pre-convention favorite for the post, supported by other railway

workers. On the first ballot, Rogers received

99 votes, Stewart had 77, and Vignes was third with 56. Since 80 votes were required for the

nomination, Rogers had captured one of the two positions. Before a second vote was taken to pick the

other nominee, candidate Charles Smith, who finished last with just 10 votes,

withdrew in favor of Stewart.