On July 4, 1885, Los Angeles celebrated Independence Day

with a parade that ended at the city hall lot at Second and Spring, where

bleachers had been built for the “literary exercises” (a reading of the

Declaration of Independence, music, singing, poetry, and a speech) that followed. The parade route was lined with as many as

15,000 people. This was probably the

first chance many Angelenos had to see the new city building after it was

completed.

A little over a month later, on August 8, Los Angeles staged

a funeral procession in honor of former President Ulysses S. Grant, who was

buried in New York the same day. A

symbolic casket was taken from the black-draped Second Street City Hall and

placed on a catafalque 18 feet long, 9 feet wide, and 16 feet high (and

bedecked with two cannons and two piles of cannonballs). It was escorted around downtown in a procession

of 1,553 people, said to be the largest in the city’s history up to that time, with

the possible exception of the nation’s centennial.

The procession’s route again ended at the city hall lot for

more literary exercises. The grandstand (seating

about 400, for dignitaries and two bands) was built up against the east and

south sides of the old School No. 1, then in the process of being torn down. The schoolhouse also had its sides draped in

black; though obviously appropriate to the occasion, it was done largely to

hide them. The grandstand itself was

draped with an American flag, apparently the largest in town, borrowed from the

State Normal School.

About 5,000 people squeezed into temporary bleachers 25 rows

high that had been built around the city hall lot and which took up half of

Second Street. The Los Angeles Times noted that the bleachers had been designed to

“easily” seat 4,000 people (with seats just 15 inches wide). Another 1,200 or more took in the scene from seats

between the grandstand and bleachers or some other viewpoint. “The procession,

the grand stand with its great audience, and the catafalque, were all

photographed by enterprising artists,” noted the Los Angeles Times the next day.

Sadly, none of those photos seems to be extant today.

If there was a swelling of municipal pride from the new city hall it quickly subsided, as problems with the building were soon evident. The City Council had recently provided the Fire Department’s Chief Engineer with a horse and buggy, but architect Young had not provided room for them in his design. On July 3, 1885, just two days after Confidence Engine Company No. 2 had moved into the engine house, it was reported that the horse and buggy were crammed into the horse-washing rack. The space was unventilated and so small that the horse could barely avoid standing in its own manure, which could not easily be removed. On July 14, the City Council voted 9-1 to ventilate the engine house by cutting portholes in its west wall (the council voted down a motion to modify the skylight in its own chamber for ventilation). What was really needed, however, was an alley along the west side of the building, with access to it from the engine house, which had no side or rear door.

So, also on July 14, the council voted to ask banker Isaias W. Hellman, long-time owner of the lot at the northwest corner of Fort and Second Street, immediately west of the city hall property, if the city could purchase the eastern 16 feet of the lot for an alley alongside the city hall (perhaps to match the width of the driveway on the north side of Young’s planned main building). Back in February 1885, Hellman had declined to name a price for his corner lot because he said he planned to soon start construction on a “handsome business block” on the property, so it may be presumed he turned the city down. However, it wasn’t until late 1887 that Hellman began building his business block on the lot at Fort and Second, and he constructed only a modest one-story commercial building on Second Street that took up less than half of the lot’s 165 feet of Second Street frontage. The structure was not built on the corner but instead right up against the west wall of the Second Street City Hall. Today, it is perplexing to read that excavation for Hellman’s building forced the city to spend $973 to underpin and protect the city hall’s west wall with a retaining wall.

On August 14, 1885, City Councilman and Chairman of the City

Board of Public Works Dr. Loring W. French – whom Young may have tried to bribe

back in July 1884 – said in a newspaper interview that the City Council had

been dissatisfied with the plans for the jail/engine house. French had voted against Young’s overall

design for the city hall, which the council had approved the previous year by

only a 6-5 vote, and now the council had seven new members. Dr. French suggested that the main part of

the city hall be built from a new design.

On September 8, City Health Officer Dr. John S. Baker warned

the City Council about the sewer connection from the city hall to the main

sewer. He said that the sewer trap was not

properly designed and needed repair to prevent sewer gas from escaping into the

building. His concerns were assigned to

the three-man Committee on Sewers, which, as far as can be determined, did

nothing. The result

was a malodorous municipal building.

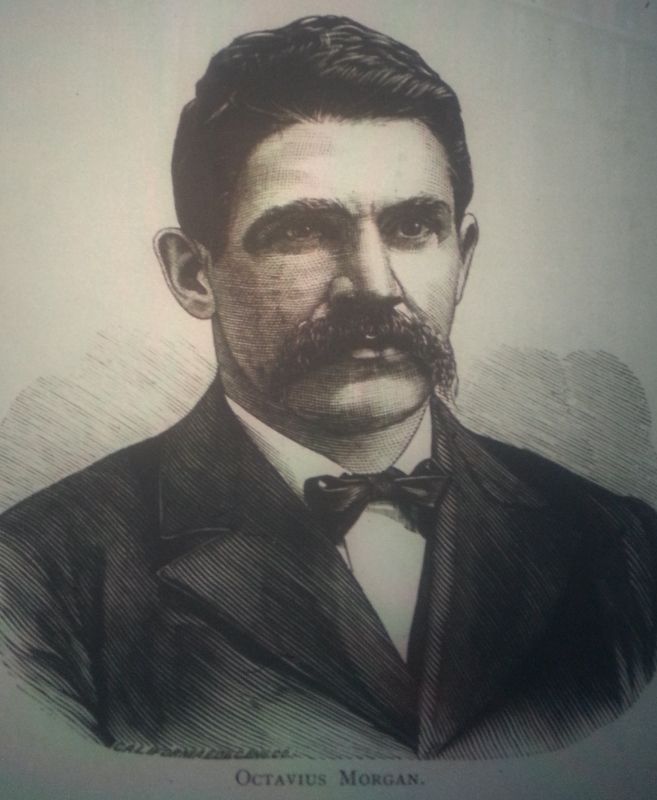

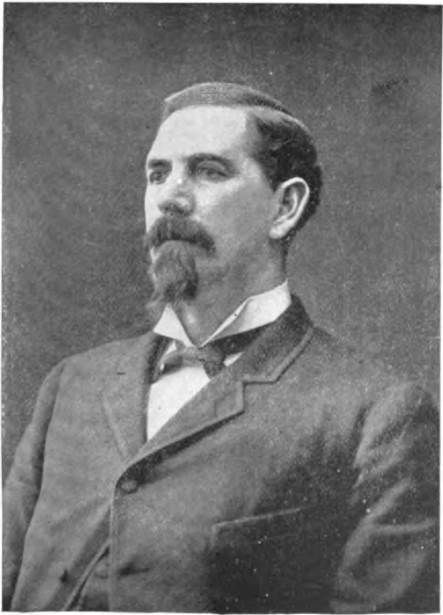

Los Angeles architect Octavius Morgan Sr. was asked by the Los

Angeles County Grand Jury (of which Morgan was a member) to examine the new city

building. Morgan spared no criticisms in

his personal report, which was made public in October 1885. Morgan said the jail was badly planned, badly

lighted, and badly ventilated, with odors from the jail spreading to the police

office and the rooms upstairs. As for

the jail cells – most of which received light and air only through a small

perforated grate -- they were “not fit to shut a dog in one night, much less a

human being,” Morgan wrote.

Morgan also said the building should not have been built on the west property line. Although this may have been the result of a poor decision by architect Young, a contributing factor may have been the exact size and location of the old School No. 1. Due to the City Council’s protracted dithering over whether to renovate or raze the old school, it was left standing while the 61-foot-wide jail/engine house was being erected. The Los Angeles School Journal of April 26, 1955, included a description of the school that appeared in “a report of the of the superintendent of Los Angeles County to the state superintendent,” apparently from 1855. In addition to being described as “well built, but not well planned” and “indifferently well ventilated,” the two-story brick building was said to be “forty by forty.” A building 40 feet square, located in the middle of the 165-foot-deep lot (as evidence seems to show the school was), would have left 62-1/2 feet between the school and the west property line. It’s possible that Young had no choice but to put the building’s west wall on the property line because the City Council didn’t finally vote to tear down School No. 1 until August 1885.

The engine house, too, according to Morgan, was poorly

lighted and ventilated. It was also poorly

sewered; the catch basins were too large, which allowed water to stagnate. Morgan did not blame architect Young for the

building’s problems, patronizingly noting that Young “had done his best.” Instead, Morgan blamed the problems with the

city building on the City Council, because if they had inquired about Young

they would have learned of “his unfitness for the position.”

|

Architect Octavius

Morgan, Sr., from the California Architect and Building News of October 15, 1886.

|

Morgan’s assessment was echoed in the official grand jury

report on the jail and engine house, also released in October 1885. The building was “improperly ventilated and

badly planned, and also badly sewered, especially the engine house. We believe a more modern style improvement

could have been built for the same amount.

We commend hereafter that more competent architects be employed.” The grand jury also recommended to the City Council

that “in the matter of letting contracts for public improvements (such as the

City Hall) greater care should be exercised, and mistakes avoided.” The Los

Angeles Herald deemed the new city hall “a failure in everything but

extravagant outlays” and said it had been “superintended by men whose

incompetency is manifest in every step.”

If being housed in a dark, stinky, engine house wasn’t bad

enough, the volunteer firefighters of Confidence Engine Company No. 2 (the Los

Angeles Fire Department, with paid employees, would replace the volunteers on

February 1, 1886) had other reasons to be disenchanted with their new but troublesome

home. With no access to the engine house

from a side alley, both the steam engine and hose cart had to be taken outside before

the hay loft could be replenished. Police

Chief Horner, next door in Police Headquarters, would not allow the firemen to

wash their hose on the sidewalk in front of the engine house. Also, the firemen had their previous building

all to themselves and had been able to fix it up exactly to their liking, but

in the new city hall their meeting room was also the City Council chamber. Although the City Council ordered molding

installed in the Council Chamber specifically so the firemen could hang their

pictures, the council ordered one of their pictures -- of a naked woman --

removed.

As it turned out, the City Council didn’t want Confidence

Engine Company No. 2 to remain in the city hall, and not just because of their

choice of artwork or the smell of their horses.

The city had been renting space for the City Auditor and City Tax Collector

in the old four-room municipal adobe at Spring and Franklin, and the property

owner, Louis Phillips, wanted the city (and county) out. On December 29, 1885, the City Council

directed that the firefighters vacate to “some proper place.” By January 8, 1886, Confidence Engine Company

No. 2 had moved back to its old quarters on the east side of Main Street, just

south of First Street. Work began immediately

on renovating the former engine house in the Second Street City Hall into

offices for the City Auditor and Tax Collector, for whom was built, using

bricks from the old School No. 1, a 7 x 20-foot vault with a bank-safe door. The new offices were occupied on April 1,

1886. The other city government

officials still had their offices scattered around town.

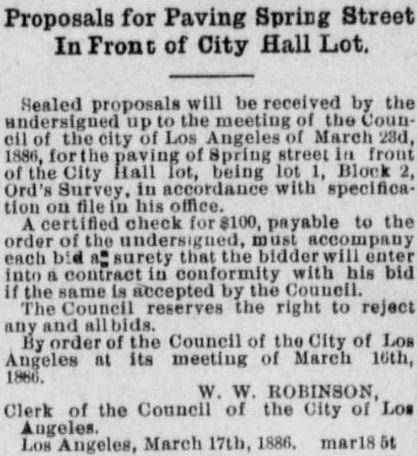

January 1886 saw heavy rains hit Los Angeles, and the

streets predictably turned to mud. At

this time, streets in Los Angeles were paved only if property owners paid to

have the street in front of their lot paved, which no one did. In the hope of encouraging property owners to

act, the City Council in March 1886 voted to pave Spring Street in front of the

city hall lot. During May 1886, 120 feet

of the west side of Spring Street was paved with six inches of concrete, topped

by 2-1/2 inches of asphalt. This was the

first section of paved street in Los Angeles (there were some earlier curbside

paving stones). There is no record of

when the street’s first pot hole appeared, but the pavement was reported to

still be in good condition in February 1887.

|

The March 18, 1886, Los

Angeles Herald carried the city’s request

for proposals to pave Spring Street in front of the city hall lot.

|

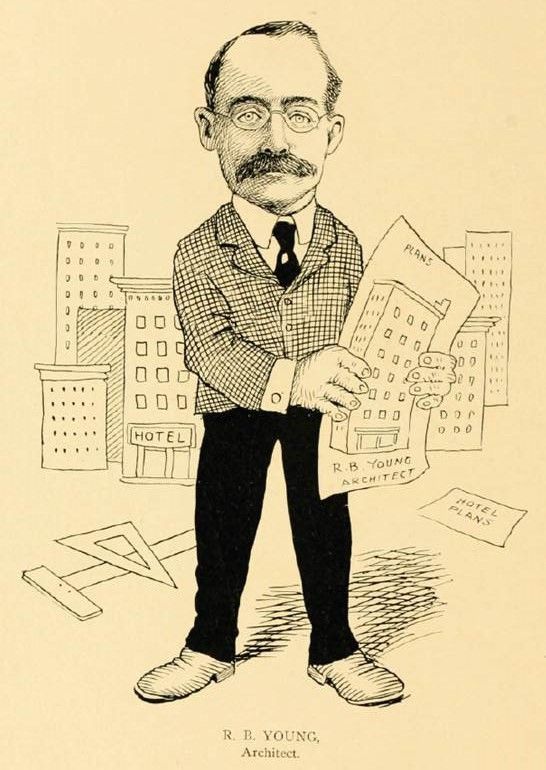

By mid-January 1886 the $65,000 in bonds for the city hall

that were approved by the voters the previous August had not yet been sold. Meanwhile, the council continued to have second

thoughts about architect R. B. Young’s overall design, no doubt fueled by

problems with his jail/engine house that had already been built. Young’s city hall plans were reviewed by the

Board of Public Works, which reported on February 2, 1886, that it did not

consider the plans “suited to the wants of this city.” The City Council then appointed a Special Committee

on City Hall Plans to review Young’s design as well. On February 9, that committee advised that Young’s

plans were not “such that the best interests of our city requires.”

Also on February 9, architect Young, undoubtedly aggrieved

at the turn of events and injury to his reputation, presented a petition to the

City Council. The text of the petition

has not survived, but it included a monetary claim against the city (likely for

work preparing plans for the city hall), as the council awarded him $650. In May 1886 the council denied his claim for

a further $350. The Second Street City

Hall must have represented one of the low points of Young’s career; it was not

mentioned in a published 1905 retrospective of his work.

|

| Architect Robert Brown Young from a c. 1900 book of caricatures. |

Ultimately, the City Council appointed a Building Committee,

which on March 9, 1886, recommended that the council invite new city hall

proposals from three architectural firms: Ezra Kysor and Octavius Morgan, William

A. Boring and Solomon (a.k.a. Sidney) I. Haas, and, again, R. B. Young. The council then voted unanimously to ask those

architects to “submit floor plans in pencil for a three-story city building,

scale one-eighth inch to the foot” (the two losing architects to receive $50

each). Young was competing again for a

job he had won in July 1884. How much

his new 1886 design differed much from his earlier plans is not known.

On March 22, the Building Committee met with all the

architects and reviewed their plans. The

next day, the committee selected the plans of Boring and Haas, and the

full council, after a cursory examination of the plans at the council meeting, approved them unanimously.

Boring and Haas were asked to prepare “elevations, details and

specifications for the new city hall, to be submitted to the council.”

At the City Council meeting on June 7, 1886, the Building

Committee advised that what were described as “general plans” for the city hall

were complete and recommended their adoption.

The members of the City Council took all of 10 minutes (during a recess)

to examine the plans before approving them.

Boring and Haas were asked to prepare detailed plans and specifications,

and the city would then solicit bids to erect the building according to those

specifications. The bids would be

divided into four parts: 1) excavation; 2) masonry of every description, terra cotta,

and tiling; 3) carpentry, joinery, iron work and painting; and 4) plumbing and trimming.

No eyebrows were raised when, on June 28, the City Council accepted

the bid of Thomas Copley to excavate the city hall lot at the corner of Second

and Spring for $.39 a cubic yard (he would be paid a total of $500). Copley’s excavation for the main city hall

building necessitated the city hiring contractor Frank C. Young at his low bid

of $1,500 to underpin and protect the east wall of the city building from any

damage due to the digging. The start of the

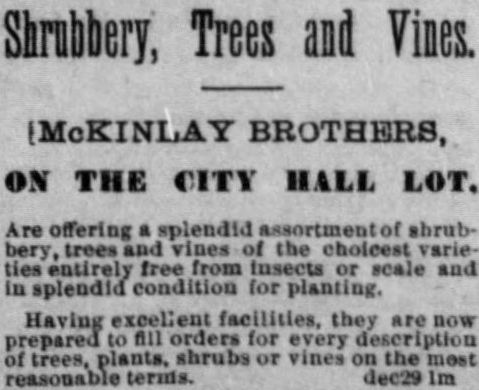

excavation on July 17 put an end to the city’s renting out space on the city

hall lot to various vendors at $22 to $50 a month.

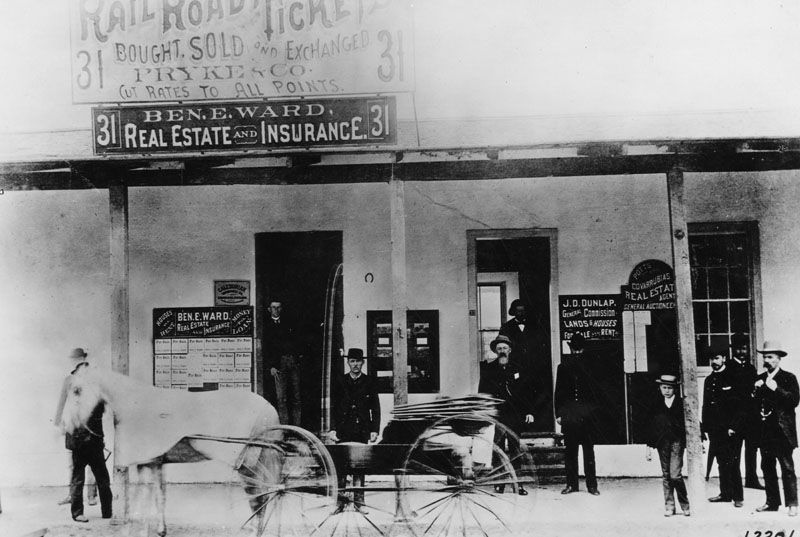

|

The December 31, 1885 Los

Angeles Herald carried an ad from one of

the vendors renting space on the city hall lot at the northwest corner of

Second and Spring Streets.

|

Preparatory to the digging, on July 14, 1886, the remaining black locust trees on the city hall lot, planted back in March 1855 to shade the children attending School No. 1, were cut down. The trees had been trimmed in late June 1885 to allow better viewing of the Independence Day exercises at the city hall lot that year.

By mid-August 1886, the $65,000 in bonds for the new city

hall that had been approved by the voters in August 1885 had finally been sold,

some of them at a premium, resulting in an additional $12,000 to the city. This extra $12,000 was put into the city hall

fund, so the city looked to be in good shape, with $77,000 to construct a

$65,000 building. Then a situation arose

that ultimately put an end to completing the Second Street City Hall.

The first hint of trouble was on August 17, 1886, when the

bids on the masonry were opened and read.

The five bids for the brick work ranged from $71,000 to $76,000, and the

three bids for the stone work were from $10,000 to $16,000. The whole

building was supposed to cost $65,000.

The next day the Building Committee met with the architects

and instructed them to use cheaper iron or brick instead of marble and terra cotta

wherever possible. The architects were

also told to use cheaper brick instead of granite on most of the building’s

first story. It was thought these

substitutions would save $25,000.

When the City Council met on August 23, the committee

reported these actions and recommended that the council reject the bids already

received. This was done, and new

advertisements were ordered placed for bids on 1) brick and stone work and 2)

rough carpenter and iron work, according to the city hall’s new, less costly, revised

specifications.

Further cause for concern surfaced at this same meeting when

Councilman Jacob Frankenfeld asked the Building Committee if the city hall

could be built for the specified price, $65,000. Councilman Jacob Kuhrts of the Building Committee

advised that it would cost $80,000 just for walls and a roof. Frankenfeld then said he had done some

investigating on his own and found the city hall would cost up to $250,000 to complete,

and he asked where the money would come from. Still, there was the hope that the new

specifications would result in significantly lower bids.

Those hopes were dashed on September 6, when the bids based

on the revised specifications were opened and read. Bids on the brick and stone work were from

$58,000 to $72,000. The rough carpenter

and iron work bids were in the $19,000-21,000 range. So, the combined low bids of $77,000 ($58,000

+ $19,000) would produce only a shell of a building. The City Council invited architects Caukin, Haas and Boring to

attend a special meeting at 7:00 p.m. on September 9 to explain why the bids on

constructing the city hall were not in alignment with the $65,000 the city

budgeted for the structure.

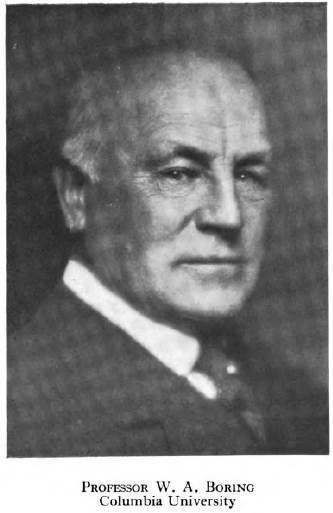

By this time, architect William Boring, who, as he wrote in

his memoir, “wanted to get into a more cultured world and know the better

architecture then being constructed,” had sold his share of the firm to his two partners. He left Los Angeles on

September 10 to study at Columbia University during the 1886-87 academic year

and later at the École de Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Eventually he was one of the co-designers of the Ellis Island Immigration

Station in New York Harbor.

|

William Alciphron

Boring (1859-1937) c. 1924, when he was the Director of the Columbia University

School of Architecture.

|

On Boring’s last night in town, September 9, he attended the

special meeting with the council, but Caukin and Haas seem to have done all the

talking (they were quoted in the Times

and the Herald the next day, but

Boring was not). Councilman Edward W.

Jones, who had suggested the meeting, opened it by asking the architects why the

city hall was going to cost so much more than the original $65,000 estimate for

their design.

Caukin had not helped with the original design back in

March, so he was able to say he knew nothing of the original cost, only that

the present plans would cost $150,000.

Even then, he added, the interior of the building would be very plain,

with soft instead of hard woods used. Caukin

also said that it was understood by the committee that the building would cost

$150,000. Councilman Jones pointed out

that the architects were supposed to be paid 5% of the cost of the building;

would that be 5% of $65,000 or $150,000?

Haas said that the original $65,000 plans had not suited

some members of the Building Committee, especially one member, and so new plans

were developed. Haas said the new plans

were shown to the Building Committee and accepted by them. He was told to go ahead with the new plans,

with nothing said regarding their cost, Haas claimed.

The “one member” of the committee Haas referred to who was especially

unhappy with the original plans may have been Councilman George L. Stearns, who

said at the meeting that there had been a general lack of awareness of the

extent of land to be built on (which seems hard to believe) and that a $65,000

building would not cover the ground properly.

Stearns also denied that he had been part of a “put up” job and said he

did not feel responsible for how the situation now stood. There was a lot of finger-pointing; the

Building Committee at the architects, the architects at the Building Committee,

and members of the City Council at both the committee and the architects. It's unlikely that we’ll ever know

exactly what happened.

The following day, September 10, the Building Committee met

with Mayor Edward F. Spence to work out the situation. The city did not have $150,000 to construct

the building designed by Caukin and Haas, but instead of directing the

architects to design a cheaper building, the committee decided to sell the city

hall lot.

At this time there was a real estate “boom” underway in Los

Angeles, and the Building Committee estimated that the lot’s 120 feet of Spring

Street frontage was worth $1,000 a foot.

The committee recommended that the full council retain the existing city

police station/jail but sell the excavated city hall lot for $120,000 and look

for a new, less expensive site to build a completely new city hall. On September 14, the City Council took those

actions. On September 27, the council

voted to auction off to the highest bidder the Second and Spring lot on

December 18, 1886, provided the winning bid was at least $120,000.

Also on September 27, contractor Frank C. Young presented

his $1,500 bill for underpinning the Second Street City Hall’s east wall to

protect it during excavation for the main part of the city hall on the corner

of Second and Spring. The Building

Committee, which had hired him, on October 4 advised the full council that

Young had done a poor job, which resulted in damage to the building (the

private office Police Chief James W. Davis was reported to have settled at

least one-half inch due to the excavation).

A three-member board of arbitration was appointed, and it sided with

contractor Young. Nonetheless, the

Building Committee subsequently recommended paying Young only $1,000 and was of

the opinion that the arbiters had underestimated the damage done to the

building and had failed “to state that the work was well enough done to fulfill

its purpose.” The matter was not settled

until March 1887, when the council voted to pay Young $1,200.

The City Council solicited sites for a new city hall, and on

September 30, 1886, the council voted to purchase a 180 x 165-foot property on

the east side of Fort Street, between Second and Third Streets, for $54,000. Construction began on the new city hall in

January 1888, and it officially opened in September 1889. The architects of that building were – perhaps

somewhat improbably – Caukin and Haas.

On December 18, 1886 at 10:00 a.m., City Clerk W. W.

Robinson tried to auction off the city hall lot at Second and Spring, but there

were no bidders at the $120,000 minimum.

Nor were there any when Robinson tried again at 2:00 p.m. Auctions on December 20 and 21 had the same

result. Finally, on December 23 –

perhaps after a bit of pleading and arm-twisting by city officials -- John

Bryson, acting on behalf of a syndicate, made the required $120,000 bid for the

103 x 120-foot property. This was the

same John Bryson who in May 1883 had bid $26,300 for the entire 165 x 120-foot

lot at Second and Spring, before the city built the jail/engine house wing of

the Second Street City Hall on the western 62 feet of the lot.

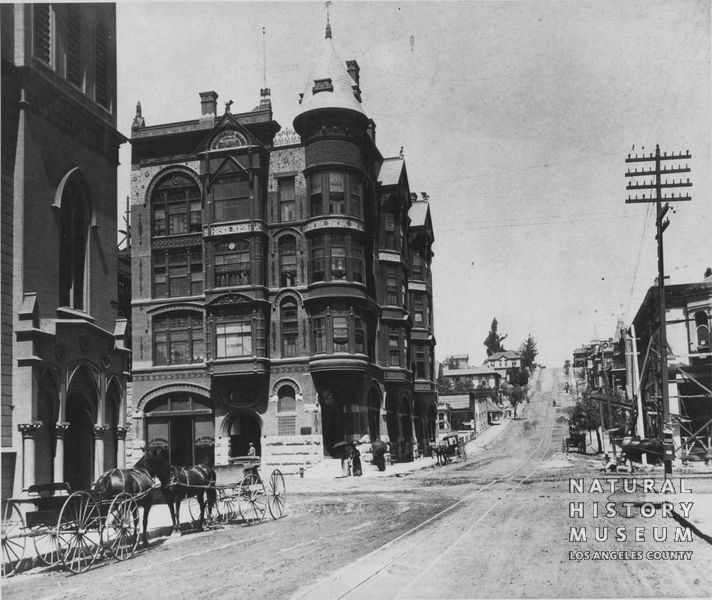

Bryson eventually built the Bryson Block at Second and

Spring, which once more required underpinning the east wall of city hall, since

the existing hole had to be deepened.

The Bryson Block, designed by architect Joseph C. Newsom, was completed

in early 1889. But from mid-1886 until construction

began on the Bryson Block in early 1888, the “City Hole,” dug for a city hall

that was never built, was a civic embarrassment.

While the debate over the future city hall continued

throughout 1886, so too did the problems with the current city hall on Second

Street. The jail cells, too few in

number and still dark and poorly ventilated, were now also routinely

overcrowded. Back on July 14, 1885, less

than a month after the jail opened, the City Council passed an ordinance that

provided for the “employment of persons confined in the city jail” – a chain

gang. The city employed its free

prisoner labor on various infrastructure projects. Increased enforcement of laws against

drunkenness, disorderly conduct, and vagrancy brought more men to the jail –

and the chain gang –

making the overcrowding worse. On December 9, 1885, 75 people spent the

night in jail, more than three times what it could comfortably hold. On January 15, 1886, there were 40 men in

jail; one cell (not the large “Corral for Drunks”) held eight prisoners. On November 5, even with 11 prisoners too

sick to work, the chain gang still numbered 51 men.

Another factor that contributed to jail overcrowding was the

practice of taking in lodgers. People

with no money and nowhere to stay could ask to spend a night in jail, and most

requests came during the winter months.

The jail housed 330 lodgers in calendar year 1886; 78 of them were in

January. A charge of Vagrancy and a term

on the chain gang could result if a person asked for lodging at the jail too

often.

The overcrowded conditions at the jail were reflected in the

Los Angeles Police Department’s monthly and yearly records. The earliest of these may be more properly

called Operations Records rather than Arrest Records, because during this era lodgers,

lost children, and other events not involving crimes were usually added

together with actual arrests. Statistics

were kept by the fiscal year, from November 1 to October 31. For the 10-year period 1879-1888, the total number

of police operations were:

1878-79 -- 719

1879-80 -- 930

1880-81 -- 945

1881-82 -- 1,323

1882-83 -- 1,803

1883-84 -- 2,166

1884-85 -- 2,471

1885-86 -- 3,214

1886-87 -- 5,194

1887-88 -- 5,994

For the 1884-85 and 1886-87 fiscal years, statistics were

published that listed the number of actual arrests, which in 1884-85 was 2,209. The top offense that year was Drunk and

Disorderly (558). A further 54 people were

arrested for only being drunk (“To Sober Up”) and another 31 for just being

Disorderly. There were 317 arrests for

Vagrancy, 144 for Gambling, and 119 for Disturbing the Peace. There were 114 Lodgers.

|

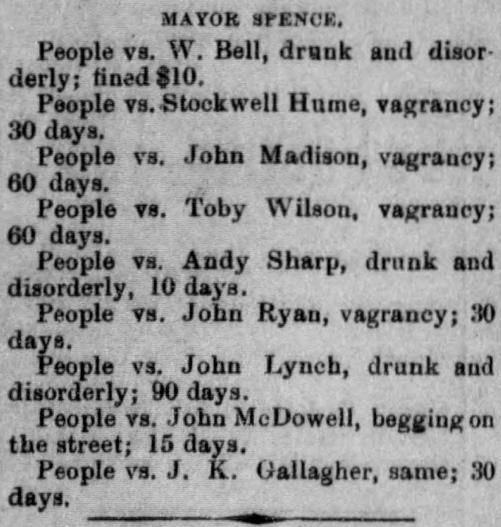

| On Wednesday, January 13, 1886, Los Angeles Mayor Edward F. Spence, in his Mayor’s Courtroom on the second floor of the Second Street City Hall, meted out punishment to the above individuals. |

By the 1886-87 fiscal year, the total of actual arrests had almost

doubled to 4,294 (on January 1, 1887, the LAPD consisted of 36 men, including

the chief). Drunk and Disorderly (890) was

again the #1 charge, although the combination of Drunk (489) and Drunk to Sober

[Up] (487) was higher. Five hundred and

nine people were arrested for Violating a City Ordinance. There were 330 arrests for Disorderly Conduct

and 270 for Gambling. Lodgers increased

to 497. The police captured more Loose

Horses (234) than Vagrants (199). There were as many arrests for Begging as

there were for Burglary (37) and as many for Vulgar Language as for Murder (4).

The first step at reducing overcrowding in the jail may have

been taken just a few months after the jail opened. A January 1886 Los Angeles Herald article on the overcrowded condition at the jail

referred to men being kept in “the cells set apart for the females.” Originally, only one of the jail’s seven

cells had been set aside for women, but two additional cells could have been

created out of that 9 x 16-foot cell by dividing it into three cells 9 feet

deep by about 5 feet wide.

A more substantial project aimed at reducing jail

overcrowding was completed in the middle of 1886, when the 60 x 20-foot yard in

back of the jail was turned into a large room.

A cement floor was laid, and above it was constructed a slanted roof

with three skylights that opened for ventilation. This new room was referred to as Cell

10. If the original women’s cell had

been divided into three, that would have created Cells 8 and 9, which would explain

why the former jail yard was later designated Cell 10.

A change to the upstairs arrangements in the Second Street

City Hall occurred in May 1886. The

Mayor’s Courtroom, previously in the room on the west side of the second floor,

was moved into the adjacent City Council Chamber. This was done to accommodate Judge H. C.

Austin’s City Justice Court, which moved into the former Mayor’s

Courtroom. Judge Austin’s courtroom had

been in the Nadeau Block, constructed in 1882-83 to be a hotel but operated as

an office building for its first three years.

Conversion of the Nadeau into a hotel began in May 1886, forcing the

court to relocate.

Another change to the interior of the jail came in June

1886, when the kitchen was remodeled to house equipment (including a 90-cell

gravity battery) for the city’s first fire alarm system. The former jail kitchen was designated

Central Station for the system, which was installed by the Richmond Fire Alarm

Company over the last half of 1886. The

system’s reliability proved disappointing during 1887, and the city kept after

the company to get the system working correctly. After the jail’s kitchen was removed, the city

fed its prisoners by contracting with restaurants to provide prepared meals,

which were brought to the jail. This procedure was more expensive, and by November 1886 LAPD Chief James W. Davis recommended a return to cooking the prisoners’ meals in the jail.

In September 1886 the jail at the Second Street City Hall

held perhaps its most notorious prisoner – albeit for only one day, before he

was transferred to the older but more secure county jail. He was Albert Baynton, the last prisoner

executed in Los Angeles County (California executions took place in state

prisons after 1891). He shot his wife to

death while she was holding their six-month-old baby, and he murdered a

neighbor, whom he brutally beat and also shot.

Baynton was hanged in the yard behind the old county jail, at the

northeast corner of Franklin and New High Streets, on November 12, 1886, just

20 days before the new county jail opened.

In March 1887, city hall architect Eugene L. Caukin and his wife adopted

one of the Baynton orphans.

Even with the jail yard turned into a large room, overcrowding at the jail continued to be a problem. In 1887, the prisoners themselves found a way to help reduce the cramped conditions: they escaped. The first six months of 1887 saw at least 19 escapes from the city jail, all the result of prisoners “tearing the flimsy structure apart,” as the Los Angeles Times put it.

In January 1887, seven prisoners escaped through the jail

yard gate (left in place and uncovered by a wall when the jail yard was roofed

over). The poor underpinning job that had

been done when the “City Hole” was dug caused the sill under the gate to

sink. This allowed prisoners armed with

a smuggled tool to cut through a bolt and open the gate. That poor underpinning also resulted in a

crack in the city hall roof, which caused much of the jail to flood in a

February 1887 rainstorm. In both

February and March, prisoners escaped by prying open the thin sheet-iron

ceilings over their cells with their bare hands and exiting through a skylight.

The cells’ original ceilings were replaced with riveted

quarter-inch boiler iron after that, but in June 1887 eight prisoners, with yet

another smuggled tool, filed off the head of a bolt, lifted up the boiler iron

ceiling, and escaped through a skylight. That October, three prisoners knocked

a hole in the back wall of the jail and escaped north through the adjacent property.

Another prisoner escaped the same way in

November. There was also an escape that

month through one of the thinly-protected skylights in the roofed-over former

jail yard.

Not surprisingly, a July 1887 grand jury report criticized

the jail as being poorly constructed and “a disgrace to the architect and to

the city.” The report also noted that

one of the walls (possibly the badly underpinned east wall) was “cracked from top

to bottom.” The dark and ill-ventilated jail

cells were deemed by the report to be more appropriate to the 18th

century than the 19th. At

night, it was impossible to tell if the prisoners were in their cells unless

the jailer lit the cells with a candle.

Even so, one cell must have been darker than all the rest, because there

are references during this period to unruly prisoners being put in “the dark

cell.”

Perhaps in response to the grand jury report, the police

made efforts to improve conditions at the jail.

In September 1887 the cells were “washed out with a strong solution of

lime water,” and the jail blankets were boiled to remove the vermin that had

been inhabiting them. The blankets were

probably dried on the roof of the former jail yard, the only place available to

do so.

On the evening of November 25, 1887, the Second Street City

Hall was the scene of what might have been the first attempted terrorist attack

in Los Angeles. A pipe bomb measuring

1-1/2 x 9 inches was left at city hall, outside the City Auditor’s office on

Second Street. After the fuse was lit,

the bomb rolled across the slanted sidewalk toward the street. The rolling may have extinguished the fuse;

in any event, there was no explosion. A

passerby, noticing the bomb but not recognizing it as such, picked it up and

brought it into the police station next door.

There, it was recognized as potentially a bomb, and it caused some

anxious moments. The subsequent consensus seemed to be that it was a hoax and

not a real bomb, and there were no further news stories about it. Nonetheless, it may not have been a

coincidence that this incident occurred exactly two weeks after the execution

of four men who were widely viewed as having been wrongly convicted in

connection with the 1886 Haymarket Square bombing in Chicago.

In January 1888 Thomas Cuddy became Chief of Police. By

the next month he took further steps to clean and fix up the jail, including

two that involved Cell 10, the former jail yard, which was used as a drunk tank. One step was to have “the bathroom in the big

cell in the rear cleaned out, so the dirtiest tramp need have no excuse leaving

the jail filthy,” as the Los Angeles

Times reported.

Chief Cuddy also established the city’s first receiving

hospital by partitioning off part of that same large room in the rear of the

jail. The hospital was supplied with two beds and some medical supplies, so people injured in

fights or accidents and brought to the station could be treated. On February 17, 1888, a prisoner claiming to

be ill used a smuggled chisel, file and saws to bore a hole in the wall and

escape from the receiving hospital. One

wonders how the prisoners continued to procure the tools they used to escape

and why the police did not search the cells more often.

In May 1888 the city approved $1,700 in changes to the

Second Street City Hall. One change was

to divide the large drunks' cell in the rear of the jail into three compartments. The area previously set aside in the drunk

tank as the city’s receiving hospital was likely effected by this renovation. The beds were probably put in one of the three new compartments, which then was designated as the

receiving hospital. News accounts during

this period refer to injured persons taken to the city jail and treated – even

operated on – in the drunks’ cell.

Another city hall renovation, completed by July 1888, probably involved removing the wall between the former jail kitchen and the vault space next to it. Responding to continued complaints about the

reliability of its fire alarm system, the Richmond Fire Alarm Company completely overhauled the system’s Central Station and installed

additional equipment in the space originally intended as a vault for offices in the main portion

of the city hall. Although the decision

not to build the main city hall building at Second and Spring had been made

back in September 1886, the vault space had apparently remained empty and

unused despite the lack of space in the jail.

The former jail kitchen remained part of the expanded Central Station.

The Second Street City Hall was a factor in the mayoral election held December 3, 1888, when banker John Bryson defeated former Councilman B. E. Miles. Voters no doubt remembered Bryson as having been the only person in December 1886 to bid the minimum of $120,000 to buy the corner of Second and Spring, where the rest of the city hall was to have been built and the magnificent Bryson Block was now being completed. Miles, who had been on the council from December 1883 to December 1885, was hurt by the fact that he’d been Council President when the city hall – by now widely viewed as a failure -- was designed, built, and finally accepted by the city from the contractor.

As 1889 opened, Angelenos looked forward to the completion

of the new city hall on Fort Street later that year. Back at the Second Street City Hall, prison

reformer and suffragette Marilla M. Ricker (1840-1920) inspected the jail in

January. She gave each woman 50 cents

and each man some chewing tobacco.

Overcrowding at the jail continued in 1889; on the morning of January

25, 1889, 73 prisoners woke up in jail, and on the night of February 10, 81

people bedded down there. An important

event in Los Angeles Police Department history took place on July 17, 1889, when

John M. Glass became Chief of Police. He

served until December 26, 1899, and he did much to modernize the department. There was little he could do about conditions

at the jail, however.

The Second Street City Hall was the scene of some notable

“firsts” by the LAPD in the late 1880s. In

May 1888 Dr. H. W. Fenner was named the first Police Surgeon, whose duties

included promptly caring for injured persons taken in or cared for by the

police. Previously, each time an

injured person was brought to the jail, a search had to be made for an

available private physician to come to the jail and treat the patient. Fenner resigned after only one month and was

replaced by Dr. James J. Choate, who served until March 1889. Choate was succeeded as Police Surgeon by Dr. N. H. Morrison, who held the office until June 1891.

|

| These photos of Doctors Choate and Morrison appeared in the Annual Report of L. E. Schwaebe -- Auditor of the City of Los Angeles -- for the Year Ending November 30, 1904. |

In August 1888 the Police Commission appointed Helen A. Watson the first Police Matron through the intercession of Mayor William Workman, who was one of the three police commissioners. Watson and Workman were among the founders of both the Girls’ Home, established in May 1887 to provide a home for destitute girls and “keep them from going astray,” and the Boys’ and Girls’ Aid Society, incorporated in March 1888 to “rescue homeless, neglected, or abused children” and provide “homes or employment and oversight” for juvenile offenders (the society is still in operation in 2018). Mayor Workman wanted Watson named Police Matron as compensation for her work with these organizations, which benefited the city. However, there were complaints that Watson seldom went to the city jail and, more importantly, did not search all women who had been arrested, a task many expected the matron to perform. When Mayor Workman’s term ended in December 1888 Watson lost her influence, and the position of Police Matron was eliminated in January 1889. It was reestablished in June 1889, and Lucy U. Gray was appointed Police Matron the next month. She served until her death in February 1904, tending to female prisoners as well as caring for needy children and juveniles.

In 1888 the LAPD acquired its first patrol wagon, built by local carriage-maker Richard Molony. In addition to carrying prisoners, the patrol wagon brought Matron Gray from her home in East Los Angeles to the jail if a woman or juvenile was detained there at night after the streetcars, for which Matron Gray had a pass, stopped running. The wagon was also used to transport people injured in accidents.

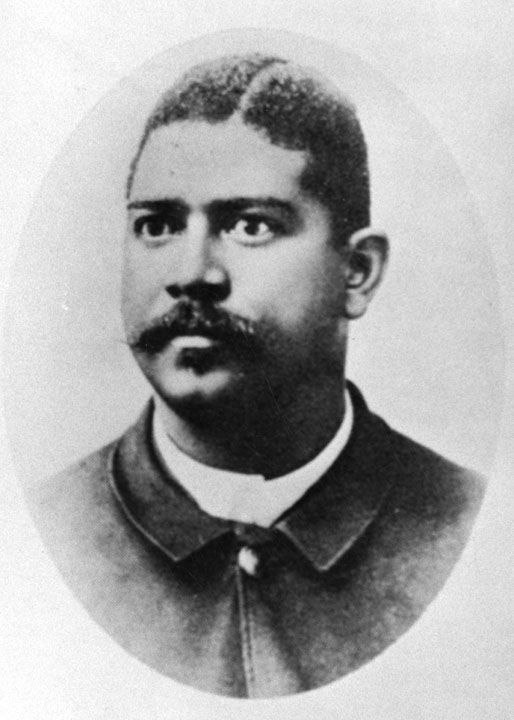

The LAPD hired its first two African-American officers on March 30, 1889: Robert William Stewart and Joseph Henry Green. Green was dismissed in February 1890 when the

police force was reduced in size. Stewart

served until 1900. On May 10

of that year he was arrested for the alleged rape of a 15-year-old white girl. On June 5, while he was locked up in county

jail awaiting trial, he was fired by the Police Commission.

His trial finally began October 22 but resulted in a hung jury four days

later (it had voted 7-5 to acquit). Stewart’s

second trial started on December 27 and ended with his acquittal December 31,

but he did not return to the LAPD. He subsequently

worked as a laborer and then as a janitor until his death at age 81.

|

| Robert W. Stewart (1850-1931), one of the first two African-American police officers in Los Angeles. |

An incident on April 20, 1889, underscored the need to find

somewhere other than the drunk cell at the city jail to treat injured

persons. A child- and wife-beater named

Frank Toal, who had previously served three years in state prison for an

assault on his wife, stabbed her six times with a small knife and might have

killed her with a hatchet if their young son had not intervened and summoned

the police. The wounds Toal inflicted on

his wife, while not life-threatening, were painful and quite bloody. Mrs. Toal was taken to the drunks’ cell at

the city jail. There, around a dozen

male prisoners who were in the same cell watched with keen interest as her wounds

were cleaned and stitched up. Afterward,

she stayed in a small closet at the jail, and when clean clothes arrived to

replace her blood-soaked ones, there was no matron to assist her.

The experience of poor Mrs. Toal may have finally prompted

the City Council to establish a true receiving hospital the next month. In late May 1889 the City Council authorized

a receiving hospital in two rented rooms on the third floor of the California

Bank Building at the southwest corner of Second and Fort Streets. However, the arrangement proved less than

ideal and only lasted about two weeks.

The elevator in the building did not run at night, making it difficult

to get patients up to the third floor.

Then in early June a man suffering from typhoid fever was brought to the

receiving hospital. When this became

known to the bank building’s occupants, they forced the removal of the sick man

from the building (to what fate is unclear).

So people injured and taken ill on the streets of Los Angeles were once

again treated in the drunk tank at the city jail.

In July 1889 the City Auditor and Tax Collector began

packing up the for the move from their offices in the Second Street City Hall

to the new Fort Street City Hall, which was almost ready to open. In August the Police Commission asked the

City Council to give the entire ground floor of the Second Street City Hall to

the Police Department to remodel for their use and to establish a true

receiving hospital that was not part of the drunks’ cell. On August 20, the council granted the request

and instructed the Police Commission to make alterations to the building under

direction of the council’s Building Committee.

Also on August 20, the City Council held its last meeting in

the Second Street City Hall. California

Governor Robert Waterman visited the old council chamber that day. The council adjourned and escorted the

Governor, who had arrived in town the day before, over to the new city hall for

a tour. On August 22, desks and

furniture were moved from the old council chamber to the new city hall, where the

City Council met for the first time on August 27. The new Fort Street City Hall was officially opened

to the public on September 18.

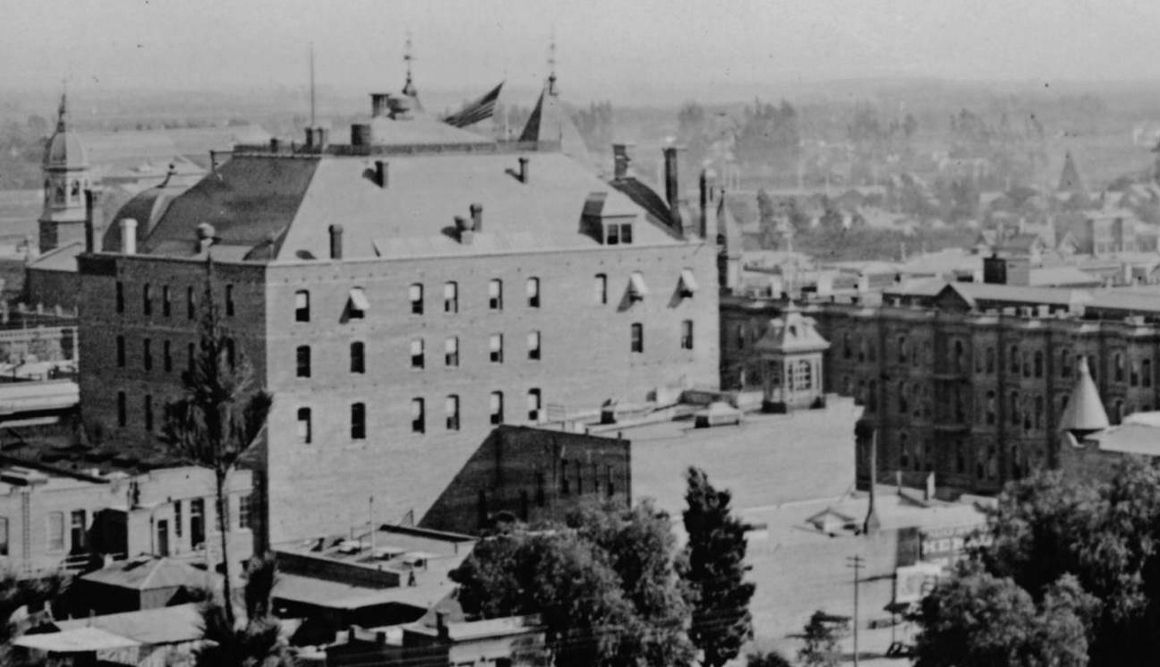

|

| We're looking northwest at the newly completed Bryson Block in 1889, with a sliver of the Second Street City Hall visible at the left edge of the photo. |

|

| This is a close-up of the Second Street City Hall from the previous photo. The City Hall window facing east toward the Bryson Block is in what was originally the Mayor’s Office. |

The Second Street City Hall was now known as the Old City Hall, and its reputation would continue to grow worse.

End of Part 2 of 4

Special thanks to Todd Gaydowski and Michael Holland of the Los Angeles City Clerk's Office for their research assistance with the Los Angeles City Archives.

If the images don't display, clear your web browser's cache and cookies, then reload the page.

Image Credits:

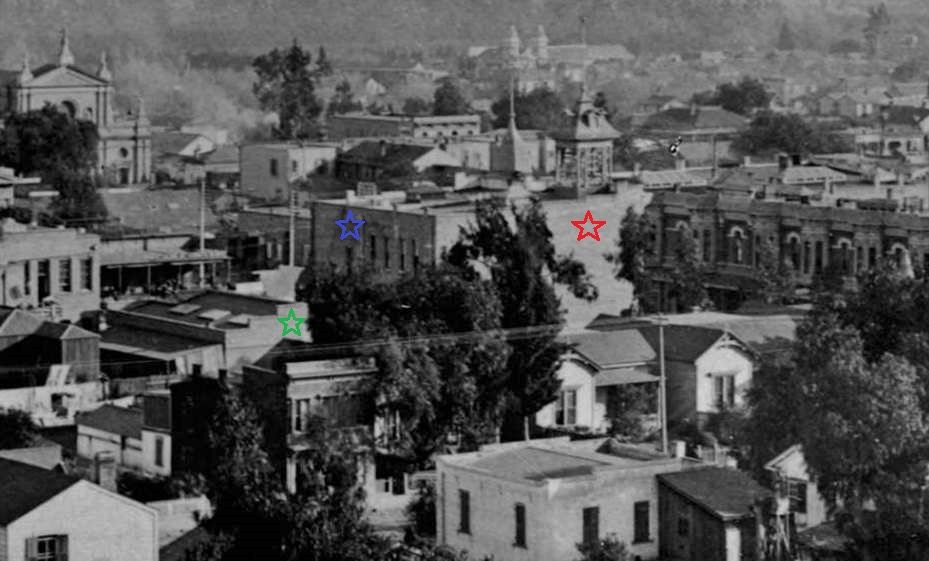

1886 looking west at City Hall: No. 113--Second St. 1886 @

UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

Octavius Morgan: October 15, 1886 California Architect and Building News @ LA Public Library

July 4, 1884 Confidence Engine Co. No. 2: CHS-12825 @ USC

Digital Library

1886 Municipal adobe at Spring and Franklin: 00059338 @ LA

Public Library

March 18, 1886 Los

Angeles Herald @ Library of Congress

R. B. Young caricature: As We

See ‘Em (E. A. Thomson, c. 1900) @ HathiTrust

July 11, 1886 Los

Angeles Times @ ProQuest via LA Public Library

December 31, 1885 Los

Angeles Herald @ Library of Congress

1886 looking SE from Court Street: 416251 @

Huntington Digital Library

c. late 1886 looking SE at city hall w/o Bryson Block:

167592 @ Huntington Digital Library

c. 1924 photo of William A. Boring: International Congress

on Architectural Education Proceedings (Royal Institute of British Architects,

1925) @ HathiTrust

c. 1890 Broadway City Hall: CHS-103 @ USC Digital Library

c. 1887 Hollenbeck Block, City Hall and City Hole: Photoantique @ ebay

January 14, 1886 Los Angeles Herald @ Library of Congress

December 8, 1887 Los Angeles Herald @ Library of Congress

January 14, 1886 Los Angeles Herald @ Library of Congress

December 8, 1887 Los Angeles Herald @ Library of Congress

c. 1887 east on Second Street: 2003-0484 @ CA State Library

1885 floorplan updated to 1888 by me

1888 Sanborn Map @

1888 Bryson Block being built: behr-0059 @ CA State Library

1888 Sanborn Map @

1888 Bryson Block being built: behr-0059 @ CA State Library

c. 1893 photo of John Glass:

Police and Prison Cyclopædia

by George W. Hale (The Riverside Press, 1893) @ HathiTrust

Police Surgeons James J. Choate and N. H. Morrison in Annual Report of L. E. Schwaebe – Auditor of the City of Los Angeles – for the Year Ending November 30, 1904 @ Hathitrust

Police Surgeons James J. Choate and N. H. Morrison in Annual Report of L. E. Schwaebe – Auditor of the City of Los Angeles – for the Year Ending November 30, 1904 @ Hathitrust

Robert W. Stewart: 00011766 @ LA Public Library

c. 1889 looking SE at city hall: CHS-2842 @ USC Digital

Library

1888/89 California Bank Building: GPF.6818 @ Seaver Center,

Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History

1889 Bryson Block with city hall at left:

Hazard/Dyson Collection A1011 @ Seeing Sunset/Islandora Repository/UCLA

No comments:

Post a Comment